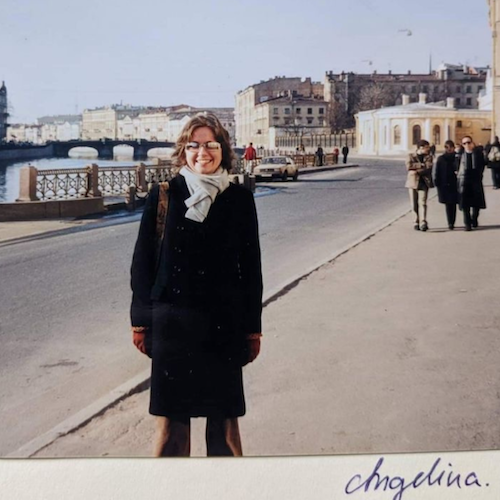

Text and photos: Angelina Davydova

AT THE SAME TIME

At the Same Time

Gleichzeitigkeit

1.

There are two cafes right by my new metro station. One serves beer and sausages – I often see fit tanned seniors sitting there sipping 0.5 lager around noon. As I am running to catch my train, trying not to be late for yet another meeting, I look at them with a feeling of incredible admiration, wishing I could learn to be as serene. Another cafe serves cakes, pastries, and ice-cream – here, there are noticeably more mothers with children and groups of young people. The ice-cream is served in the glass bowls and is topped with mountains of berries and whipped cream – it must be scooped out of the bowl before this melted tower starts dripping straight onto the table.

Late in the evening and even more so at night, both cafes are closed. The only place open during the night hours is a 24/7 Turkish-owned fruit and vegetable store where you can also buy some other basic products and order a coffee to go. At night, a homeless woman often sits on a bench near the station with her packed bags and a pram. The woman sleeps right there on the bench, sitting. A wiener dog that goes unnoticed at first glance lives in the baby carriage, and peeps out of it curiously examining the passers-by, sometimes barking at them. I left this woman some food once – she did not wake up, the dog silently examined me. Next time I tried to give her some money – it was already late, around two o’clock in the morning. The woman thanked me but confidently refused the offer. The dachshund barked at me, backing up the stance of its owner. That same night, I saw a string of slowly moving luminous circles in the sky. It reminded me of a scene from Close Encounters of the Third Kind. For a long time, I stood in the park next to my building, head tilted backward, looking at the object that turned out to be Elon Musk's network of Starlink satellites.

The other day, I spent two hours in the ice cream parlour near the station with my friend N. who travelled from the Ruhr area to Berlin to attend a conference. We first met 20 years ago and last saw each other in 2008. We did not keep in touch regularly and only exchanged the most important news.

In 2002 she graduated from her high school and came to Saint Petersburg to do her internship. Once, she got lost downtown and walked for hours ending up in the outskirts of the city. She walked a lot then, trying to get to know a new city and a country, the language of which she hardly spoke, through reading the writings on the walls of the buildings, among others.

Now N. practices her somewhat rusty Russian with a family of Ukrainian refugees who lived at her place for a month and a half. She has already arranged a new apartment for them and a place in a kindergarten for the eldest of their two daughters. N. and her husband have three sons, a big house, and a big cat. She teaches German literature at a local university and has now come to Berlin for the first large-scale offline conference since the start of the pandemic.

At some point in our conversation over the ice cream N. recites these two lines from Hermann Hesse's poem "Steps":

Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne,

Der uns beschützt und der uns hilft, zu leben (1)

“A rather teenage writer, actually, but this particular passage strangely resonates with the current situation,” she says confidently.

I remember how many lines my close and distant friends have posted since the beginning of the war, and how many new poems they have written themselves. As if it is through poetry and religious texts that one could find the meaning of what was happening.

One came back to poetry after several years of non-writing, another suddenly began to quote the Bible or the Torah. In a bar at a contemporary art center Winzavod in early March, my friend A. went over the lines trying to remember what was written in the Talmud about the murder of one and many. It was a cold spring. In a bar that looked like a light-filled dacha, customers talked mostly about the war. Snippets of their conversations, like puzzles, came together in my mind, forming a picture of powerlessness.

"What has happened in your life in the last 20 years?", N. asks me.

But the last three months have erased these 20 years; they are nothing more than pure record now. The present turns the past into a list of events, relationships, and movements from one place to another. Last September, I moved into a new apartment. By the end of January, I had finished going through the boxes of diaries, stories, and drawings, putting them on the shelves.

In the beginning of March, I packed 1,5 suitcases of essentials to get me started, and left.

The future is hidden by a heavy curtain that no one can peek through. Neither cinema screen nor theatre stage can be seen behind it. A year and a half ago, V. and I wandered around the Kirov Palace of Culture, a monument of constructivism on Vasilyevsky Island in St.Petersburg, once built as a true "palace of culture" – with cinema halls, theatres, library, dance studios, and sports clubs. Already then it had been partly reconstructed with craft food, designer clothing, and jewellery markets on the weekends. While guys with well-groomed beards were selling fenugreek cheese and necklaces made of recycled wax paper on the first floor (with beard cosmetics found on the neighbouring counters), the second floor remained a dusty domain of the temple of bygone knowledge. Instead of the closed library with its books given away to the residents of the surrounding houses, the space was occupied by a second-hand furniture store.

There, among the sofas and the “made in the GDR” wall cabinets, giant vases about a metre high were on sale - it seemed that they could hide a grown man. The store also sold taxidermy animals: foxes, badgers, and bears. The shop was run by a tall, silver-haired woman dressed in a denim suit and cowboy boots. She told us about the mistakes the architects made while planning the building - for example, how water stays on the long rectangular balconies not pouring down and how melting snow floods the building. “Constructivism here was in the form, not in the essence,” she said then.

The woman guided us through a labyrinth of stairs, showing an unfinished observatory, dressing and fitting rooms of the little theatre on the top floor, ballroom dance hall, and, finally, a movie theatre with a collapsed ceiling. We saw rows of joined red chairs with boards and plaster on them - all this was covered in snow. Then, the view of the cinema hall made me freeze for a couple of minutes, experiencing a heavy feeling of pity for the place mixed with reverence. The landscape of destruction, sounding like a single note, was the very picture that was so often shown on the screen in this hall when it was still a cinema.

I did not dare to take a photo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair (2)

2.

Only a few cafes and shops are open on an island of Heybeliada in the Sea of Marmara near Istanbul in mid-March. In most of them, the TV is always on. Salesmen, sometimes with friends, children or grandchildren keeping them company, sit behind the counter, smoke, drink coffee, pet fluffy cats and very fat dogs that look more like calves. News number one is always the war in Ukraine. While my friends are buying local wine in one litre bottles, and cigarettes, I can't drag myself away from the screen.

Before, in my previous life, in the hotels and airports, I saw the destruction of cities in other parts of the world on television. Now, I recognize these panel houses. I myself grew up in one of them at the outskirts of Saint Petersburg.

The area was informally called “the Merry Settlement” and it was considered a dangerous place to live in the 90s.

Four years ago, I took my American friend A. around the neighbourhood where I spent my childhood. She found it very quiet and green. Indeed, it has changed. New multi-storied houses were built among the existing ones from the 1960s-1980s, on wastelands, in green courtyards. Some of them were surrounded by a fence that can only be opened with an electronic key available to the residents. New bright-coloured playgrounds appeared among the houses as did the chain stores and coffee shops in the long nine-storied buildings along the main transport highway.

The highway takes us out of the city, up to the overpass, and further down into the forests and fields where some years ago an IKEA store opened, and now it is closed for good.

Through the arches of the nine-storied buildings one can get into the inner passages going along the five-storied Khrushchyovkas and rare Nadezhin houses or "dot houses", as they are called, "scattered" right in the middle of lush green areas in accordance with the very bright ideas of adjective city planners. Now, as there are fewer green spaces, the residents do their best to preserve them. During my childhood, the battle was not for the trees but against them. People demanded for the trees to be cut down, or the heavy green branches to be cut off, the ones that stood in the way of the much wanted light shining into the windows of ground floor apartments.

From the windows of my room, overlooking the playground frequented by mothers with children and local drunkards, I could see a five-storied house that looked exactly the same as ours. In the windows of the last floor, one could see the reflections of a slow sunset with the panes lit in golden colour. In one of the rooms the TV was on, illuminating the windows from the inside. I used to come up with the stories about the life of the apartment residents and acted them out with the dolls I had. It was impossible to see the real life of the neighbours through the windows, especially at this sunset hour. Looking at the illuminated windows, I also imagined how the sun was setting on the other side, behind the houses, the bridge, and the river. It was the most beautiful time of the day.

Many of the people who make decisions about the bombing and siege of Ukainian cities at this very moment grew up in the same neighbourhoods.

Thou shall not. Does this help now?

After the footage from the scenes of hostilities on Turkish television, an expert discussion begins. Analysts in suits are discussing the possible options of further developments.

I myself take on this role sometimes.

We choose some aspect, abstract our minds, “expand the perspective”. How can one do this while being an insider and outsider to the story at the same time and talk about something else rather than feelings? How can one sit up still?

Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still (3)

3.

At the beginning of June, we sat with Y. in Bonn on a wooden platform near the former Bundestag building - now the site of one of the UN conferences. We dip our feet in the grass still wet from yesterday's rain. The delegates, resembling herons, move carefully on the lawn talking on their phones under the embracing early evening sun. Italian, English, Chinese. On the grass, all languages intertwine and follow running black birds occupied with their search for fresh insects. To the right, behind the fence that encloses the building, is the Rhine embankment with the joggers, cyclists, and passers-by taking photographs – I will join them in a couple of hours. You can hardly see the river from where we sit, but we know it is there.

Y. reminisces about her life in the Moscow region in January 1993, when they, a group of German schoolchildren, came to Troitsk on an exchange trip and lived in Star City (Translator’s note: Star City, also known as Zvezdny Gorodok, is a closed urban locality associated with space training). She focuses on seeking out all the elements of the cosmic reality of that time in her memory, and remembers the Russian school kids who were their exchange partners. Some of them lived in small, book-filled apartments in high-rise buildings. One girl's family lived in their own giant (as it seemed then) house where once a farewell party took place. At that time life was opening up and expanding. In 1989, the first American exchange students came to my school as well. In 1993, instead of history lessons, we discussed the ongoing political events in the country.

Now everything is moving backwards.

Y. does not say it out loud, but the question “how can this be happening now?” haunts our conversation. Until recently, Y. was occasionally in touch with some of the participants from that school exchange which happened almost 30 years ago via Facebook. In late February, one of the former Russian schoolgirls published an anti-war statement. Then everyone stopped posting.

Late at night, by the hotel entrance, I ask a man in a wheelchair for a cigarette. When he finds out that I am from Russia, he starts talking to me in Polish. Actually, he is from Qatar. He is engaged in the development of Paralympic sports and he came here for a few weeks to visit the International Paralympic Committee. He learned Polish because he likes the language. He was in a car accident 20 years ago and has been unable to walk since. We talk a lot about the war, he keeps patting me on the knee saying that I must be strong, I can be strong, I can walk, and I can make a future, a different future.

Getting back to my room, I go through my friends' messages on Telegram.

L., a friend from St.Petersburg, stopped communicating with her parents because they support the war. She does not even take her son over to their place for the weekend anymore. I write that I sympathise with her. “People in Mariupol are having it worse,” she replies.

Some urban activists from Saint Petersburg that I know say they see no sense in protecting the cultural heritage anymore. Another friend V., an environmental activist from an industrial Siberian city whose inhabitants breathe the air poisoned by the emissions from the four metallurgical plants, writes that he sees no point in fighting for clean air anymore. V.'s mother does not believe his reports on what is happening in Ukraine. She chooses to trust what is being said on Russian state TV.

In mid-April in Berlin, E. asks all of us sitting at the table what we live for now, what reason we can name.

I, I wish you could swim

Like the dolphins, like dolphins can swim

Though nothing, nothing will keep us together

We can beat them, for ever and ever (4)

4.

“I’m not really worried about myself, I have seen worse, but how can I keep my daughter from going to the rallies and protests? I cannot lock her up. She wants to go, she is against this, but what does the future hold? I can be silent - she cannot, "K. told me right before my departure from Saint Petersburg. A daughter of another friend of mine had already been detained twice by that time, always at Gostiny Dvor department store on Nevsky Prospect, and she had her first trial the next day in the Vasileostrovskiy District Court. The district assistance group collected water and food for the detainees, human rights groups helped with the lawyers, activists came to the court and to the temporary detention centres where the convicts were sent to serve their sentences, to find out if there is anything they can do to help.

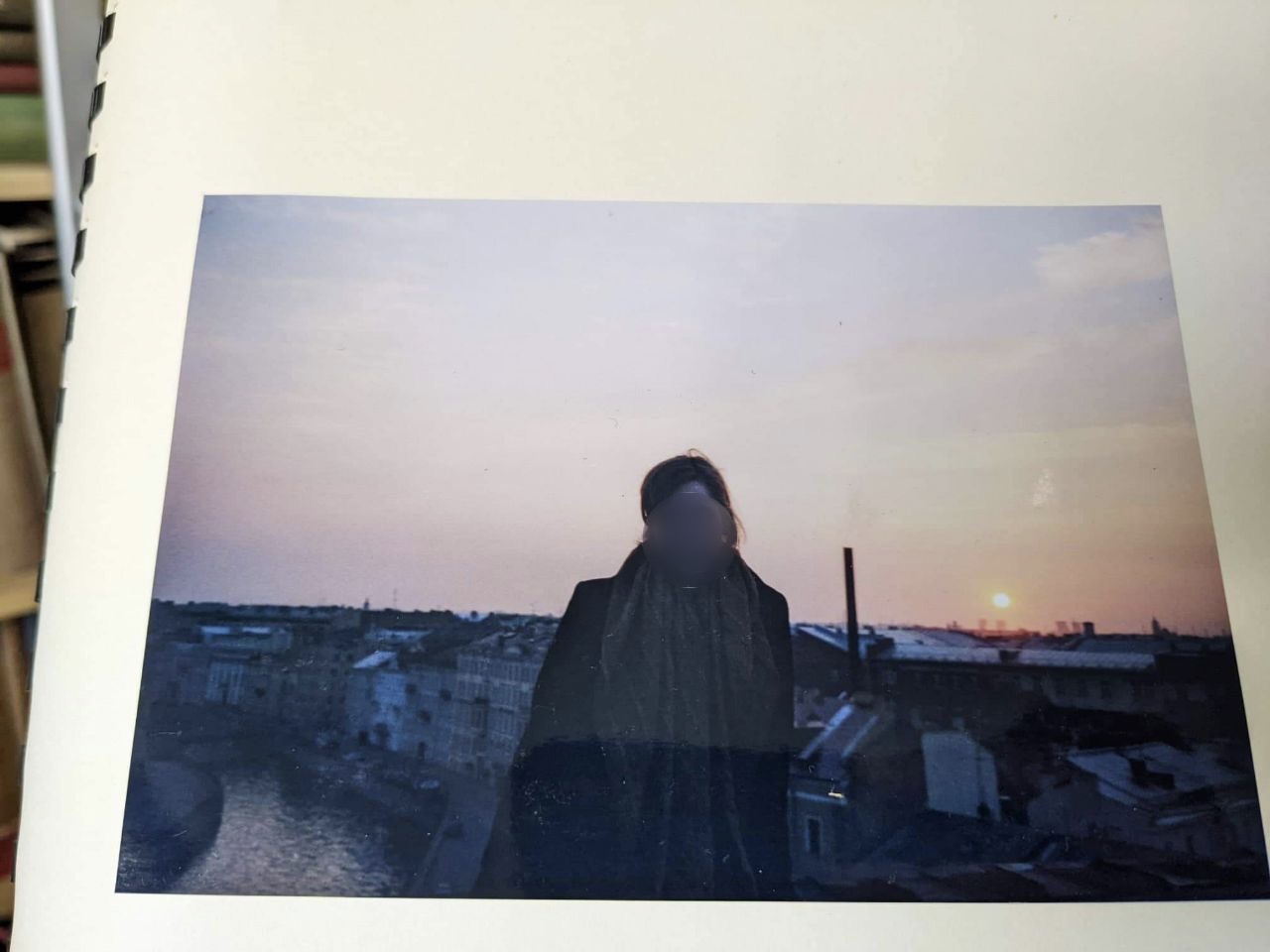

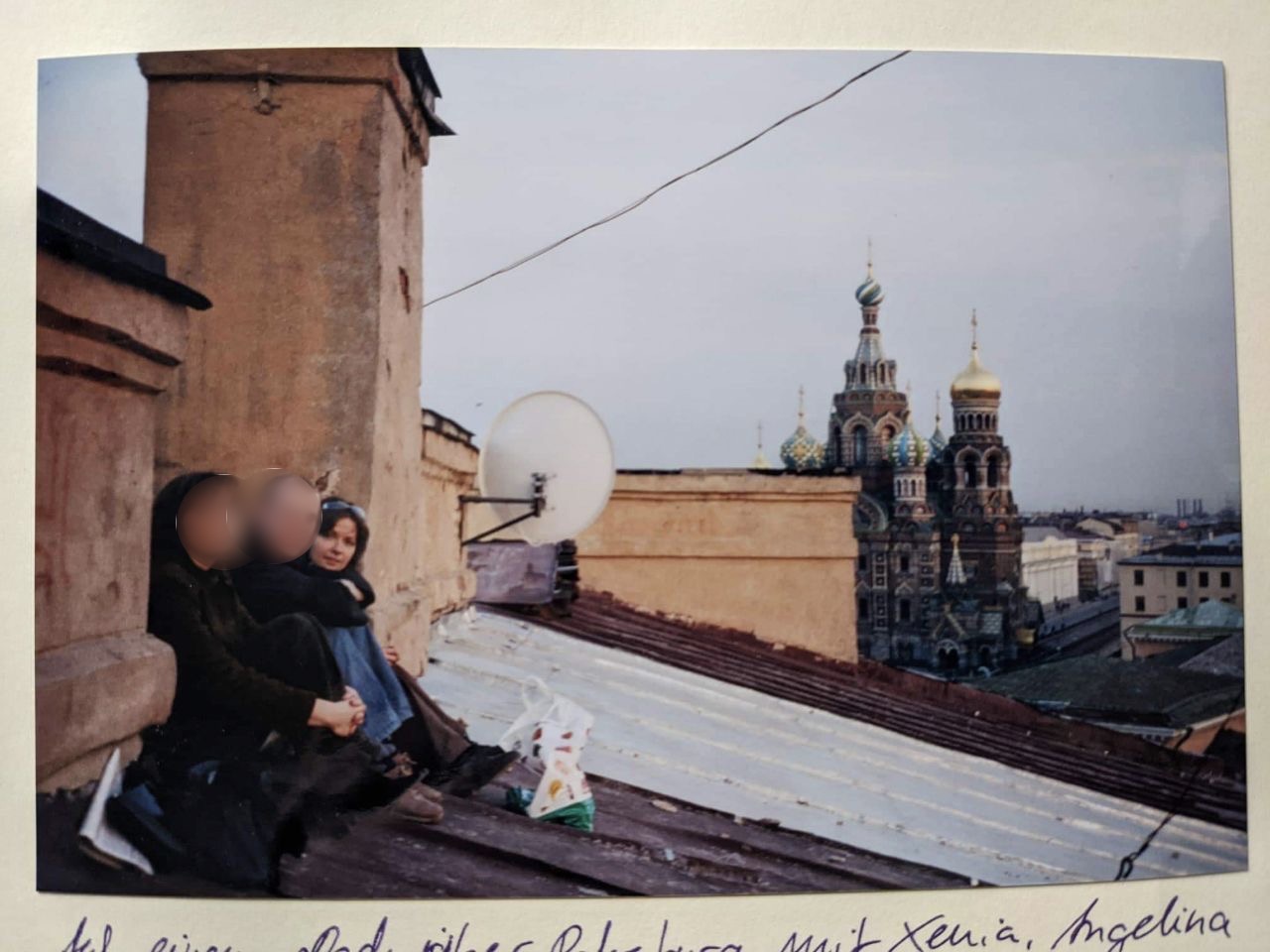

For N., Petersburg 20 years ago was the city of discoveries. Back then, I played the role of a slightly older friend in her life - taking her by the hand and leading someplace new: to the balconies, basement bars, rooftops, and art galleries.

I remember how I brought her to the rooftop of the house where Daniil Kharms once lived. Recently, the city authorities painted over the graffiti with his image to replace it with a light projection. Many years ago, I was investigating the details of the poet’s death, trying to understand whether he died in Novosibirsk or in Leningrad - later, the researchers confirmed that Daniil Kharms died of starvation in Kresty prison hospital in Leningrad.

Before I went to primary school, I spent quite a lot of time not far from the Kresty pretrial detention in the Leningrad Regional Children's Clinical Hospital. There, in spacious wards with high ceilings, among an abundance of white colours, with the green flowering garden in the yard, and a detached dark green building where children from Ukraine and Belarus were taken to after the Chernobyl disaster, I created a special world for myself. My doctor Vladimir Ivanovich was a part of this world. He knew how to speak with the parents of the children on eye level and was always confident in the uniqueness of each child and individuality of each case. The expression "children with special needs" was rarely used then.

5.

In recent years, I became a frequent guest in a small bar on Vasilyevsky Island in Saint Petersburg. Among the regular visitors, there were many doctors, actors, geologists, and people of unidentified professions. I listened to their conversations and made notes, thinking of writing either a play or a story about their failures and their ways of dealing with these failures.

Doctors talked about the difficulties of working with cancer patients, or about visiting families where domestic abuse was taking place, or about psychological challenges of their patients. Some of them talked about how difficult it was when patients see you as an Almighty God in your efforts to save them. Some of the bar visitors wanted to stop practising medicine and become, say, a film director – this career change unexpectedly did not work out for one of the regular guests. Another frequent visitor used to be a musician and had recently lost his job. He came there to sing, to drink, and to talk about his problem to the others.

That play or a story would have been called Sympathy for the Failure as the bartenders would often put on a Rolling Stones concert with Mick Jagger singing

I stuck around St.Petersburg

When I saw there was a time for a change (5)

In recent weeks, the owner of the bar who from time to time also plays the roles of a bartender and a chef sends me videos from the bar. It seems that nothing has changed. The same view from the window, the same bar counter, the same familiar faces. They smile and wave at me through the phone camera. They send their greetings.

6.

It is difficult to line up the events of the past 20 years on a chart of the long-term trends. That is why questions about time spans make me think about what and why I am doing here and now. This is exactly what my American friend L. once asked me about. It is with her that we discovered the world of the art squat (a house squatted by artists, now an art centre) Pushkinskaya-10 in St. Petersburg in 1999.

L. left the city in the spring of 2000. I saw her off at the old Pulkovo airport in St. Petersburg. She kept peeking out from behind the doors of the passport control wall to wave at me. We didn't have mobile phones back then.

The next time I saw her was in September 2014 in New York at her birthday party in a bar on the roof of one of the skyscrapers overlooking the 9/11 memorial. In 2001, she wrote me a detailed email describing her thoughts and experiences of that day. I read it out loud – as a testament to the history of her present and of the world happening now. In the spring of 2022, she wrote to me again, asking where I was and what was happening to me.

From the second floor of a country house on an island near Istanbul on a snowy March day, I tried putting the events of my life into words in English to send her the same report. In response, she sent me long letters about her everyday life in Minneapolis, her husband’s participation in a teachers' strike, and accounts of what her children did at home while on school break. About the houses she designs. Also about the snow.

For me, these letters created a picture of an ongoing reality that is growing and building up somewhere, far beyond the Bosphorus, outside the house and the island, in a different time zone where my evening ended in her morning.

7.

N. tells me there is a pumping station opposite the house where she used to live. It was not until recently that she discovered its purpose. The city where she lives is located in the Ruhr region, once the centre of the coal mining world. This legacy left its long-term imprint in the form of undeground voids. The voids are easily filled with water from streams and rivers, which, due to the geological subsidence, cannot follow their natural course. The water would literally have to move backwards, upstream. That is why people use pumps. Otherwise, the Ruhr area would have turned into a “lake district”. The costs for the infrastructure are called “eternal costs” (Ewigkeitskosten). “We, humans, are in the trap of our time and its simultaneities. Therefore, in the worst case scenario, the actions of people lead to the need for “eternal costs,” says N.

Terraforming, that is how it is called now. Terraforming. People changing the Earth. And the ground beneath their feet.

Her city is growing, people need more and more housing. That is why a city forest not far from N.'s house was cut down. “You know, there are fewer birds, you can literally see it - and hear it,” says N. as we walk along the canal.

A week later, an amusement park opens near my new home. One evening, I walk along the merry-go-rounds, mirror pavilions reflecting in each other, shooting galleries, and slides interspersed with cafes selling beer, ice cream, corn, and bubble tea. Everything shines, rings, and sparkles; you might not notice Elon Musk’s satellites in the sky. The water in the canal nearby flows quietly, and you can’t hear the birds.

There is a movie plot when characters, getting into an amusement park, find themselves in some kind of a parallel universe where the colours are brighter, the magical creatures roam about, and people can become superheroes. As I pass throught the fairgrounds I see childen excitiedly speaking German, Turkish or Russian, mezmerised by the rides soaring and spinning people through the air, and I think that the imaginary reality has come to an end, that one can no longer escape. The only thing left is to face this hyperreal world - through a mirror that does not endlessly reflect in other dimensions.

Fantasy worlds are temporarily unavailable. They are closed for an inventory check. It is useful to learn to face the "here and now" with open eyes, looking outwards and inwards simultaneously.

8.

So much has been happening in the recent weeks that it's hard for me to keep track of all the events, people, and stories. Here I am sitting in a coffee shop in Mitte, it has just rained and passing cars are splashing water. I am having a cup of coffee and notice a blueberry muffin in a glass display in the cafe. That reminds me of a very similar place in St. Louis, Missouri, the city with the Gateway Arch. It was there in that cafe that I had breakfast with my friend, a journalist from Hong Kong, every morning for the whole week in 2016. We ordered a similar coffee with a similar cake, read the news, and observed the tram tracks repairs taking place right outside the window. Last November I saw him in London. He told me that he had to leave Hong Kong a few months ago. I did not know that I would follow in his footsteps so soon.

Now, people around me and I find ourselves in an intermediate state. Between legal statuses, different types of visas, documents, and rights. We wait, we keep waiting, we learn to wait. We barely know one another, but we become flatmates, or give each other instructions in case of a sudden death. This is so different from the previous experience of long-lasting and patient relationships that we had in the previous life, when you could know someone for 20 years or more. Everything is moving faster now.

Last night I walked along the wall of the Berlin Zoo. There were many memorial plaques attached to the wall, dedicated to the men and women who restored the zoo after the Second World War. One of the plaques was dedicated to Katharina Heinroth who ran the Berlin Zoo from 1945 to 1956.

Translation:

Katharina Heinroth, ethologist and Germany's first female zoo director

“It all started with the moths”

From 1945 to 1956, she was in charge of the restoration and rebuilding of the Berlin Zoo, completely destroyed during the Second World War. She introduced people to the “wonder of nature”.

Ukrainian ecologist A. who analyses the environmental consequences of the war is working on a long text about the rare plants that can disappear as a result of military activities; about burning forests, destroyed zoos, and the animals that died not having a chance to escape. In a semi-business correspondence, he casually sends the photographs he took of the March shelling of his city in the Kyiv region. In these pictures a flame from a burning oil depot covers the sky. No sky to be seen, it is all fire.

“While I was choosing a photo for the publication, I was amazed myself – this all happened in just four months,” he writes.

“I'm afraid to look at the pictures,” a Russian colleague replies.

Nennt man die besten Namen,

So wird auch der meine genannt (6)

9.

Some weeks ago, my friend E. introduced me to The Hat, a jazz venue in Berlin that, accidentally, turned out to be a ‘sister’ bar of a similar place in Saint Petersburg. We sat outside observing the simultaneity of movements in the night surrounding us. Yellow and red S-Bahn passenger cabins rumbled, a black car, barely visible in the dark, quietly turned around, a long-legged cyclist speeded up, an airplane, seen as a white dot in the sky, flew by. An escalator brought down differently dressed people with different hair styles: some were walking down the stairs, some were standing still, looking at their phones. A grey crow ran by, clouds came together, the leaves of city trees trembled a bit. The sounds of people's voices telling each other stories from Lebenszeit und Weltzeit hang in the air around us.

E. then said it works in a similar way in jazz.

I think about what else is happening in the world right now.

(1) Hermann Hesse, Stufen

(2) T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

(3) T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

(4) David Bowie, Heroes

(5) The Rolling Stones, Sympathy for the Devil

(6) Heinrich Heine, Buch der Lieder