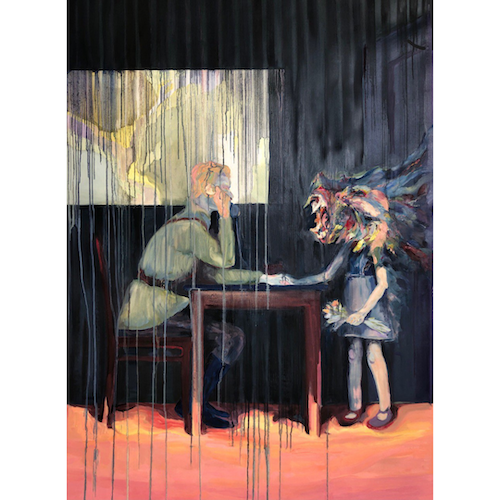

Text: Adel Kim

Artwork: After, 2022, oil on canvas, 140х100 cm (an interpretation of Border Guard by Yuriy Gorbinov, 1969. Project in progress)

Text: Adel Kim

Artwork: After, 2022, oil on canvas, 140х100 cm (an interpretation of Border Guard by Yuriy Gorbinov, 1969. Project in progress)

When we started the Reside/Sustain project, we focused on the potential of art residencies to enable sustainable development practices in Russia and Finland. Today, it is obvious that the project needs a revision of its key concepts. If earlier in the context of contemporary art "residing" was to a large extent associated with residences, what does it mean for a Russian cultural professional now? How to stay resilient right here right now? To what extent adapting to circumstances in order to survive is possible?

This is the first in a series of interviews where I talk to Russian artists from an array of different life circumstances brought about by Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine. I'm interested in what "to reside" and "to sustain" mean to them today. It is important for me to hear and amplify the voices of different actors, study different points of view, and try on different perspectives.

The first interview is with artist and activist Mika Plutitskaya who works on the topic of "Soviet childhood". In her works, she reflects on themes of collective and personal memory and explores Soviet cultural representations, architecture, movies, and illustrations. She focuses on the study of painting as a post-medium. Mika is an advocate for a feminist critique of gender representation.

Mika has a Bachelor's degree in Fine Arts from the University of Hertfordshire and Bachelor’s degree in psychology from Moscow State University. She has participated in the 2nd Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art “Beautiful Night for All the People” (2020); “Open Systems” (2015), “Global Activism” (2014), “Performance in Russia: Cartography of History” (2014), “International Women's Day: Feminism from the Avant-Garde to the Present” (2013). In 2014, she organized feminist workshops "Kitchen" for contemporary artists with the support of the Rosa Luxembourg Foundation. The artist has had solo exhibitions: “Like a Merry-Go-Round in Childhood”, Artwin Gallery in Cube Moscow (2020); "Typical project" at CCI Fabrika (2020).

Since March 2022, Mika has been living in Yerevan, Armenia. The interview took place on May 15th, 2022. By then, she was waiting for the results of her master’s degree application to the University of Leipzig. In the autumn, she got accepted.

The delay in publishing is due to safety concerns.

Adel Kim: What is your artistic practice and what did you do before the 24th of February?

Mika Plutitskaya: I am working with critical rethinking of the Soviet heritage and, in particular, Soviet visual culture from the perspective of the present day and my generation. When the initial shock (of the onset of war) wore off, I pulled myself together to think about what I was doing and the doubts about my work being irrelevant disappeared. I realised that I should have been doing ten, a hundred, or a thousand times more and that there is no need to change my approach and topic radically. The war revealed what I felt before—violence under the cover of Soviet culture, cinema, painting, and rhetoric. I was sometimes told that studying Soviet culture is no longer relevant since it has already passed, so it is like pouring from empty into the void. But I didn't feel like it was over. Rather, it can be compared to the Chernobyl disaster: the radiation was contained in a “sarcophagus”, but it continued to spread. It always seemed to me that Soviet culture is a huge chunk of polluted cultural soil that has never been fully processed and that is why it continues to exude this cultural “radiation”. As a result, certain people, vested with power, decided to open the sarcophagus.

Before, I dealt with the background of Soviet culture attempting to show that behind the harmless surface of nostalgia hides the reality of untreated violence. Now it is plain for all to see. It is not just a ghost that manifests itself and then disappears. The ghost has turned into a ghoul that kills people. It is scary.

I became fully convinced that this ghost was never safe. I was right in my premonition that I needed to do this. If the past is not dealt with, ghosts materialise.

AK: I had an intuitive thought about the Soviet. History cannot repeat itself and what is happening today does not mean a return to the Soviet past. Moreover, it makes impossible the very possibility of return, by crossing out these 30 post-Soviet years. Ideology, slogans, and affirmations that were taught to us at school became inapplicable and forbidden. This can be compared to a cover used to hide buildings that are being reconstructed. I have a feeling that there is nothing behind this cover, but somehow it holds.

MP: I do not quite agree. I do this because I come from a family that practised this “Sovietness” as a religion. My grandfathers, both deceased now, were intelligence officers who worked for the GRU, and my understanding of how traumatised everyone is comes from my family’s experience. Once we discussed with the students where everyone grew up and it turned out that half of the group was from the former Soviet closed cities. It seems to me that the problem is that this, unfortunately, is not just an empty appearance. Structures live inside people. You can replace the word "communist" with "Orthodox", but look how fast the denunciations began! I understand that people are scared and disoriented, but this readiness to report someone for not speaking patriotically enough, for something they have said; this willingness to snitch startles me. Until this readiness to tattle was activated, it had been “hibernating”. But once the permission for violence is obtained, it comes back easily. Which means it has been there. Or the rhetoric that others are ready to attack us, that we are against the whole world, that there are enemies around—this was used by Goebbels’s and Mussolini’s propaganda, but in our culture it is Soviet, Stalinist.

A façade is just a façade, but as long as there are people helping hold it up, it will not fall. They say: no, this is something dear to us, we do not want it to fall. Even if it is ugly, dusty, crooked, it is uncomfortable for us to hold it, it makes our backs hurt, children are hungry, dinner is not ready, we cannot wash ourselves, we feel bad, we still stand and keep up this damn facade. For me, it was ridiculous and absurd until tanks began appearing from behind the façade and shooting at people. But something makes people keep holding it.

AK: What has changed in your professional and personal life since the beginning of the war?

MP: The only thing that has not changed is my willingness to work with the same topics. Although, perhaps, it has also changed: I realised that some things need to be done in a tougher, sharper, more articulated and frank way. Not creating propaganda posters, but referring to the representations of ideology directly, and not, for example, to personal stories of women. Now I allow myself to work more spontaneously and expressively than before. This is in terms of artistic practice.

Apart from that, everything has changed. I spent a week in Moscow trying to figure out how to live and what to do. As an artist, I had a feeling that there were only two options for me: starting an activist struggle and, if I am to stay in Russia, speaking out against what's happening. Or I have to leave the country because it is impossible to remain silent. Since I felt it was very dangerous to speak openly about what was happening and it could affect me physically and mentally, I decided to leave. Even putting activism aside, I am sure that not everything I do can be shown in Russia. I do painting and at the same time I am involved in a photo project (I won’t share the details since it has just started and there is no result as of now), but I’m sure that no one will put it on view in Russia. As long as the existing regime is in power, showing some of my works will result in a breach of the Russian criminal code and consequences for me or a venue. I understand that I can’t work as an artist there, except perhaps as a closeted one.

The only thing I could do in Russia is teaching. And if for some reason I have to live there, then I will do it, and definitely not in Moscow, but the regions. I don’t know how realistic this is, but this is the only meaningful option I can imagine. However, first and foremost I would like to be an artist, so I decided that I would try to leave.

AK: How do you like working in Yerevan? Is it difficult to adapt to life in a new place?

MP: It is hard, really. There were some practical issues, but I managed to sort them out. It is difficult because of my psychological state. Although I am much more comfortable here than in Moscow, and I feel that I am not going literally crazy anymore, I still wake up and read the news in the morning. Now I came up with a solution: I read the most painful news in the evening to have a chance of getting something done during the day. It does not always work. Emotions overwhelm you. Sometimes all you want is to lie down and scream. There is rational, and then there are emotions that make you want to leave everything behind and go to the border with Ukraine to volunteer. It is clear that there is no good answer to the question of what needs to be done. I try to set boundaries for myself, what I can and cannot do. I tell myself that I will go to Leipzig where there are plenty of Ukrainians, and volunteer there. Many people offer help in Moscow: some Ukrainians are taken to Russia, and there are volunteers there who help refugees to leave. Sometimes I think: why am I doing this useless art? It would be better if I went back to Moscow and started volunteering. There are moments when I read, for example, a report about a guy who buries and exhumes bodies in Bucha, and I just sit and cry. It is not in my power to stop this. The only thing I can do is being a witness, read the news and posts of Ukrainian friends, listening and accepting the things they say. Even if these are the calls to cancel the entire Russian culture.

AK: From the very beginning of the war, you were quite active on social media and did not mince words.

MP: Really? I feel I spoke out very little; cautiously, and cowardly. Maybe it is perceived differently from the outside than from the inside. I posted in the beginning, then at some point, I fell into a state where I could not publish anything. I still have a hard time posting on Instagram. This is not about art as a whole, but rather about the Moscow contemporary art scene as a system, and how people use social media, how I used to do it. I realised how narcissistic these self-representations are. I realised I cannot keep doing it the old way. I cannot write that I have an exhibition opening tomorrow. Both Facebook and Instagram [recognised as extremist organisations in the Russian Federation—A.K.]— are about showing off how successful you are. I realised I don't want this anymore. I just read that The Sixtiers artist died of starvation in Bucha and I don’t understand how to post selfies now like I’m doing fine and having delicious food in a cafe. That was a difficult realisation.

For some time, I wrote very little and did not understand how one can write at all. To this day, I have a feeling I am not vocal enough. At some point, I just wanted to cry and ask for forgiveness. But that won't stop the war. I read posts Ukrainian artists wrote. Anatoly Belov posted something like: “Dear Russian artists, you do not need to write to me that you are against this. Get up and go outside. I need you to protest to stop the war.“ He has the right to say this. But I also understand that people cannot stop it. We find ourselves in a situation when the Reichstag is on fire and Hitler is in power. Unfortunately, today going out to the streets with a blank piece of paper leads directly to the prison cell.

I thought a lot about this. It feels like we were all bribed at some point. After all, there was the annexation of Crimea, everyone was against it, everyone said it was a crime. But we were asked: do you love your job? Nobody forbids you from doing it. Can you continue with your feminist horizontal educational initiatives, your art? Then do it. And we went for it. I understand that there are people who are personally responsible for the war, people that will be imprisoned for war crimes (I hope there will be a trial). But I'm guilty, even if my share of the guilt is one in one hundred and forty-million. My taxes, my participation in this infrastructure. I envied those who left after 2014, many of my friends did. They understood everything, it was the last straw for them. For me, it was February 24th.

Not everyone can leave. People are against the war, but they cannot say anything, they feel horrible. I admire many psychologists I know because they say: not everyone will leave. We need children to be raised by adequate people. We need life to go on, and rightly so. I am inspired by people who stay and continue doing something.

AK: So you do not intend to return?

MP: I will not come back until there is a trial for those who started this. But we do not know how that willhappen and whether it happens at all. There should be a trial, not for the sake of executing someone. The problem is that what should have been done in the 1990s or early 2000s was not done. There were things to be condemned. Not to imprison some old men who worked in the NKVD in the 1930s, but for an internal process of rethinking the totalitarian experience to take place. This, unfortunately, did not happen. Either Russian culture will do this and continue to be human, or it will be reborn into something horrible.

AK: Have you managed to blend in into the circle of local artists and galleries in Yerevan? There are many Russian artists there now, for sure.

MP: There are a lot of Russian artists, and they, like me, need to wrap their heads around what is going on. Everyone's image of the future collapsed, plans were cancelled. It is unclear how to live, how to support oneself, how to work. There are a lot of questions.

I cannot say I have integrated since I do not know the language. Although everyone in Armenia speaks Russian, you need to speak Armenian for the proper integration to happen, and it takes time. I do not learn Armenian because I have an exam in German in a month (another colonial story). I am happy, I have met new people, seen something new, expanded my experience, and know that there is another culture still unfamiliar to me, but I have been lucky enough to touch the surface. Here, one could start the conversations about decolonialism. For example, the second language in Soviet schools was either French or English, but not Armenian, Tajik, Kazakh, or Lithuanian. At the same time, in all the other republics, Russian was compulsory in schools. And we, Russians, need to comprehend this.

In Leipzig, I might have an interesting experience. But it would be better if we did not have a reason to leave, it would be better to continue working where we started, and with our own topic.

AK: Do you continue cooperating with your gallery? Is everything more or less stable in this regard?

MP: I do, but I think the market must have collapsed. They approached me with an offer to make an NFT project and I'm ready to try, it seems interesting. I am in a situation where I do not need to sell anything to make a living. I do what I think is right in relation to my practice.

AK: You mentioned that you are in touch with Ukrainian friends and colleagues.

MP: I contacted several activists recently. I wanted to do it for a long time, but I could not go forward with it. I had doubts about what I would even write? But I finally did. They all replied: Mika, thank you for reaching out, it was important. We know that you are against the war. Perhaps I needed it more than they did. I had doubts, I thought that to much time had passed and there was no point in contacting them anymore, it was too late. But I decided to go for it. In the end, they have every right to tell me to get out of their face or ignore me. I just felt the need to do it and it made me feel better.

These were the people with whom I communicated professionally and worked on different projects with. I tried to find words to make it about them, not about me. But it was definitely better to go for it because now I feel there is still hope. Despite the huge gap, dialogue is possible. And I am very grateful to the Ukrainian activists for this.

АК: It is important that you are the one starting it. We all are…

МP: Knocked out.

АК: Exactly. When we support the silence, it becomes mutual. As help or aggression can be mutual, so can silence.

MP: I thought: who should be the first one to reach out? Not them. I decided I was prepared for any answer or no answer at all. I think that Ukrainians have the right to any reaction or comment directed at my country, me personally, my language, and my culture. My job is to listen to what is being said and try to be a part of it, sharing the horror. There is nothing else we can do except for being with people and living through this experience.

АК: During this time, every one of us has developed strategies that help us to not lose our minds and try to understand how to react to what. Strategies that didn’t exist before. Do you have some?

MP: I'm not sure if this counts as a strategy, but going back to what I said about the narcissism of the contemporary art system, I realised I need to talk less about myself, my status or my career, and more about the cause. At some point, I realised that in this catastrophic situation and from the point of view of values, narcissism is garbage that can be thrown in the dumpster. This realisation helps a lot. Every time you feel scared, you start thinking about the cause. Inwardly, I waved goodbye to all my claims for exhibitions and projects. I said to myself: I will be grateful for any opportunity to continue working, whatever it may be. I switched to the idea that there are people who are ready to help me, people who care. I am grateful for any display of humanity. I realised that being grateful for every kind gesture helps a lot in coping with horror. Even this interview is real support. This is an opportunity to talk and realise that you exist. I understand that many people are missing this right now. I know this pain from my conversations with students: they have just started their journey as artists, and they already have the feeling that everything has been shut down, that they do not exist at all. I feel it too, it is scary, painful, and hard.

Being grateful helps. There is a lot of humaneness around, and it can manifest itself in very simple ways. When you walk down the streets of Yerevan, people can see you are not a local. They ask where you are from and where you live, and when you answer you are from Moscow and say the name of your metro station, they say: “Oh, it is a long way to go, here is a metro token for you.” Or you are in a crowded minibus, standing as all the seats are taken, and someone who is sitting says: “Let me hold your bag, I can see it is heavy.” There are many examples. I notice them consciously, keep them in my mind, and go through them in the evening; saying “thank you” again to those who helped, and trying to do something nice for others.

That's all we have. How else can we defeat this masculine, patriarchy? You cannot stop a moving tank. Standing in front of a tank is a bad idea. It is heroic, but it seems to me that this tank wants our sacrifice. It was created to get as many victims as possible, so we should not help it achieve its goal if we have a chance. Some say it's cowardice. But we already know what it means to close an embrasure with our bodies. We should learn to love, value, protect, and take care of ourselves and the people around us. There are times when you need to get up and go against this tank, for example, if it threatens to kill your child. But if there is the chance, it is better to take the child into your arms and get out of the way.

AK: It seems that in a crisis situation, by definition, one has to sacrifice something. We have been brought up surrounded by this heroic narrative, although we do not understand who needs it from us and why. What you say about loving yourself and learning to love others, understanding the value of life — this is not about heroism, but about humanity.

MP: I am happy that even though many people support [the war], there are no queues at the military registration and enlistment office. Volunteers do not rush to the frontline.

I wish there was an understanding in my country that we don't have to stay up all night to do something. For people to have the dignity to be indignant and say: why does my well-being depend on a crazy old man? The understanding that we should not endure anything for the sake of the great goals of the great strategist who decided to prove something to himself. Why do you need greatness when you can live a normal, ordinary, and prosperous life?

Another personal strategy is to ask people how they are doing. It is very difficult for me to do since normally I write to people only about work. But now I'm trying to ask, listen, and communicate. Being professional in your work also helps: I want to do my job properly, and consciously. When you are not physically present in a familiar environment, there is a feeling that you are going off the radar. You existed, but not anymore. Writing "How are you?" is the way to deal with it.

I also try not to be mad at myself for being inefficient. There are days when getting vaccinated and cooking dinner are the only two things I manage to get done in a day. You need time and space to cry; things that you used to do quickly take longer now. You need to understand that you are in a very difficult situation, dealing with a lot of stress, so try not to demand five posts, an academic text, and a painting from yourself in one day. You also come to realise that the main objective is to survive. Doing things and praising yourself for doing them: taking care of yourself, having food, sleeping. The second objective is to keep moving forward. You did something, you praised yourself. And the third objective is helping other people: you helped someone, you praised yourself. If you do these, you are doing well. Less ambition, fewer claims, more love, and support.

AK: Yes, I can hardly work at all.

MP: Same here. I do things, but if I compare them to the amount of work I used to do three months ago, it seems I am doing nothing. Sometimes writing a post on social media takes me three hours. I do my best, but it is very hard.

I do not feel completely safe, I do not understand what else can happen. So we need to do things to feel safe. I think I am very careful in my statements. I look at people who can do more—for example, Mikhail Durnenkov—with admiration and respect.

I often feel like my words are trivial and worth nothing. Sometimes I ask myself why I write at all if, for example, Kirill Rogov has already written a hundred much better texts. But I read a very important text on syg.ma, a report by a sociologist who researched Nazism. He conducted interviews in 1947, visited Germany, and spoke with locals who survived through everything. One of his messages is this: when there is a public consensus on euphemisms, it is very important to have people who call things by their real names: terror, repressions, and crimes. It is important that ordinary people say this. After reading the article I realised I need to say these things out loud as often as possible even though it seems to me that my words are banal and obvious, I feel like an idiot, and it is hard for me.

I think that in many ways the goal of Putin’s team is to silence everyone. It's horrendous. It is hard for many people; they do not want war and feel like complete shit. I think people in power want you to feel this guilt for being a coward: people are being killed and you are afraid to go to a rally. I have a lot of knowledge and experience of abusive relationships within families. These are the same patterns, very similar to ones a domestic abuser employs. The first thing an abuser does is convince family members that they are nothing. That they are insignificant, bad, trivial, have no power to influence things, will never be supported, and so on. So that you lay down depressed and do nothing. This is what we and the whole country are experiencing currently. This is yet another crime. I understand that we have more responsibility since we belong to an educated and privileged group. People who receive 20,000 rubles [around 300 euros at the moment of interview - A.K.] a month are not to blame for anything. Nobody asked them.

Another interesting story is the narrative that the state supposedly gave us something for free. This is a complete lack of boundaries between people and the state; not knowing that money does not belong to the state, but to us, as it comes from taxes. It's a complicated knot of boundaries, and the idea that someone owes something to someone. If you are doing a performance sponsored by the state money, you must serve the interests of the state. Why? Foreign artists do not think this way: if they receive a grant, they will not create a project someone ordered them to do. Our state considers itself entitled to dictate.

I think no one in power really cares about contemporary art, it is not popular culture like cinema. But I am terrified they will come to our soil too. They will give money only for very specific things. The attitude towards contemporary art in society is negative because there is a lack of knowledge and education in this particular field. It would be great to include it in the school or university curriculum. I am sure that contemporary art is a great subject for high school students, for example. A good friend of mine teaches at a private school. Children's eyes light up when she talks about the projects of contemporary artists. Students need to have a tool to start thinking about it, and the rest they will figure out themselves. This is a layer of visual culture which is not represented and not spoken about in schools. For many people in Russia, contemporary art does not exist simply because it is impossible to “count” it.

It doesn’t take much to figure it out, get interested. Art is cool because it impacts you emotionally. I hope at some point we will be able to do this. And that we will not be too old when this finally happens.