Text: Adel Kim

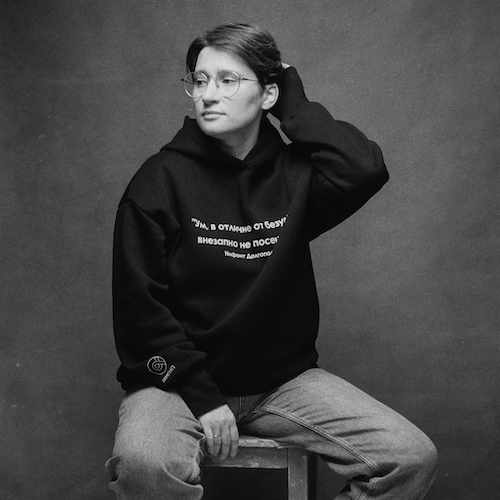

Photo: courtesy of Olga Sorina

Text: Adel Kim

Photo: courtesy of Olga Sorina

Sustainability is not limited to questions of the environment, social and economic prosperity. Implementation of sustainable development strategies within art institutions and residencies is directly related to the certain people responsible for making decisions and implementing them. Often their role is somewhat dissolved; lost in the general activities of the organisation. However, it is extremely important that they maintain their ability to fulfil these work related duties.

In this interview, Reside/Sustain participant Adel Kim discusses issues of personal resilience in art residencies, with Olga Sorina – psychologist specialising in burnout issues, and founder of the “Vdokh” psychological centre. Olga consults and supervises employees from various NGOs and other industries, and manages socio-psychological projects. She is also the author of the book “This can be done: avoiding burnout while helping others” (“Nuzhna Pomosh” charity foundation, 2023).

Adel Kim: I know first-hand what burnout is. I would formulate my feelings as “I have been tired from the beginning of time and haven’t been able to rest since then.”

This fatigue was connected to my work in an art residency where processes of dealing with artists, their arrivals and departures, well-being, and creative activities depended on me. This led to the lack of proper weekends, boundaries between professional and personal, the inability to rest while on holidays, and the impossibility of relaxation. Without noticing, I ended up in very bad shape. Not until my position was terminated was I able to see the situation clearly. Needless to say, I was taken aback.

In the work of art residencies, an artists’ arrival means more than a professional transaction. It involves building personal connections, and getting involved in a process of care from which a residency worker's profession takes root. I noticed that many of my colleagues do not draw a line between work and personal time, they do not discuss their limitless job duties with the management, they dive into work with the utmost dedication and motivation and, as a result, put themselves in a risky position. I wanted to start this conversation so that my burnout experience could help others avoid it.

I came across the concept of “helping professions” and learned that professionals in these fields are especially susceptible to burnout. What are these professions and why are they riskier than others?

Olga Sorina: “Helping professions” are professions that involve taking care of others. Initially, this group included doctors, social workers, psychologists – those who work with people with various health conditions, emotional distress, and difficult life situations. For them, the main task is to help and support. If we think about “helping professions” more broadly, they include everyone who works with people, especially in close contact and on a long-term basis, including residency workers.

What is common for these professions is the burden of emotional stress. All of us are subjected to emotional stress to a certain extent, even if our jobs do not include a lot of interactive and assistance tasks. However, these are central for “helping professions”. If the emotional load is taken away from the equation, the profession will lose its meaning. This is why people in “helping professions” often risk getting burned out.

What adds to the risk is that the emotional burden is still not considered a significant stress factor – neither by management and organisations, nor by the professionals themselves. The list of stress factors may include busy schedules, the number of tasks on their plate, and the inability to separate work and personal time but they rarely talk about the stress that comes from being in contact with people who experience difficulties of various nature.

Let's imagine that some challenging situation arises while artists are in residency. They decide to bring it up with the residency worker. How do you know if they expect this issue to be solved by the coordinator, or just want to share their pain? If this is not agreed upon in advance, residency professionals tend to proceed based on their own experience and ideas that are shaped by, among others, the relationships within their own families, social interactions etc.

If we are taught to be good listeners when someone feels bad, we will listen, even though we are not trained psychologists and cannot help them. There is some emotional support involved in professional activities. However, it is quite limited: “I feel for you, what can we do?“ However, if professionals take it more personally, then problems may arise. On a personal level, we are not ready to cope with such stress; as the joke goes, “life didn’t prepare us for this“.

АK: Do you say that people involved in professions that are associated with emotional stress, should ideally be prepared for it?

ОS: I work mainly with Russian organisations and professionals and I can say that only psychologists are trained to deal with emotional stress in Russia. Such training is neither available for social workers, although their work with clients is a heavy emotional burden, nor included in medical training. Now, further vocational education on dealing with patients, relationships, and patient compliance exists, but it is not widely available. Therefore, it is really beneficial for social workers and doctors who come to me to get help. It is enough for professionals to study three theoretical pieces on how to work with beneficiaries and patients, for them to start behaving and feeling completely differently. They finally start to understand how the process evolves and the situation develops. After this, the next step is to start building boundaries.

АK: I can project this onto my experience: until you realise that you are faced with a real additional – emotional – burden, you think you are the problem; that you have not worked hard enough or performed professionally enough. It seems this attitude is even encouraged by organisations. It is beneficial for them when an employee works more, believing that problems occur as a result of their own mistakes.

ОS: I do not think this is beneficial for organisations – they lose people because of it. If an employee leaves, they need to train a new one, and it is difficult and expensive in the long run. I agree, however, that until you are aware of the stress you experience, it affects you unpredictably. Moreover, you do not have the tools to help you reduce stress and survive it.

Interactions with residents that cause stress, are part of the employee's responsibilities and cannot be avoided. Therefore, one possible way to deal with this is to reduce the emotional load through organisational decisions. This includes building general agreements regarding boundaries – for example, set working hours and proper work-free weekends. Another way is to look for options to soften the load and help professionals withstand the weight. In this case, schooling on how relationships work is efficient. Emotional support is also needed: residency workers should have the opportunity to discuss controversial cases, or to share their worries about the residents: for example, how getting along with some residents is easier than with the others; and how residents that we develop friendly relationships with, can start demanding things that go beyond professional boundaries.

АK: I understand this example is probably from some other field, but it applies so well to the case of art residencies.

ОS: This is a matter of professional relationships common for “helping professions”. It is important to draw a line between professional and personal. Firstly, professional relationships only go one way, not both ways. In friendship, reciprocity is important, however the goal of professional relationships is to benefit the client – or, in this case, the resident. The residency worker is there for the residents.

Secondly, these relationships are limited in time. Friendship has no expiration date. The “coordinator-resident“ relationship is finite: there is a concrete timeframe with end date, although there are sometimes ways of keeping communication open even after the residency is over. The beginning and end points are very important. When the end point is unknown, it becomes an issue for professionals.

Thirdly, professional relationships always have some purpose, unlike friendship or love. At work, it is necessary to understand what is being done and why. If you look at professional relationships this way, it becomes easier – the employee’s tasks come down to some very specific activities: ensuring physical safety, comfort, and access to materials. Of course, communication is also involved, but it follows a purpose: even meaningless chatter may be a way of pursuing the task of establishing or maintaining contact with the residents.

Professionals must understand the purpose clearly, and decide what to include in their relationships with their beneficiaries. Residents have many needs: working comfortably, socialising, having a good time, sightseeing. There are always more needs than one can satisfy. Professionals should not try to fulfill everything that is asked of them; they should clearly understand what needs are within the scope of their professional competence, and which are not. For example, listening to some painful personal stories of a resident will not do anyone much good since residency workers are not mental health professionals. Of course, it will provide some outlet for the resident, but it will happen at the expense of staff’s energy. This will not make them feel any better, nor will it benefit their work.

In professional relations, the focus should be on the client's benefit. However, while working towards this goal, it is important to keep theemployee’s well being in mind, and to avoid situations where the clients overburden staff with their various needs. The employees, in turn, often do their best to satisfy them all at their own personal expense. This behavior is common in some families, and we bring it with us into work relationships. When the number of people, whose needs the employees have to satisfy, is 20 or 30, this is when the employees are faced with some potentially challenging situations.

When professionals understand their responsibilities, they have to communicate them to the people they work with and manage expectations by making clear what they can deliver, and what falls outside of their work duties. When employees refuse to do someone else’s work, it is not out of malice, but simply because they realise their own limits. They might be able to listen, but no good will come out of it, and for professionals, it is important that work interactions produce some good. It is worth looking for clear ways to explain this to people, to respectfully outline the boundaries, highlighting the will to help, but also the limitations: functional, hourly, territorial.

АK: This requires a critical audit of one’s own abilities. It often seems that if you just listen as a fellow human being to what the person has to share, even if it takes three hours, it will somehow help them. It is crucial to remember that, as you mentioned, this will not resolve the situation. Maybe the person will eventually feel a bit better, but at your expense; but, the situation will not be resolved, as you are not competent to assist in matters of a private nature. This is a humble process of realising you are not omnipotent.

ОS: “I can do something useful“ is a bad motto for professionals. What can you do exactly? How does this match the organisation's goals? What are your personal objectives? What is the benefit for the resident? Maybe there is another professional who can help in situations of private nature more efficiently? Three hours of one’s life are important —you’d better spend them working with things you do best, or living your life, if it is outside of your working hours.

In the best case scenario, “helping professionals” would get proper training and clearly understand the benefits of what they bring. Residency workers can discuss the criteria for evaluating their work, and how to understand that they really do benefit the resident. These criteria, by the way, may be different for the professional community and beneficiaries of their work since the former have a deeper professional understanding of the benefits. The beneficiaries do not usually have the same level of understanding.

Moreover, professionals can rely on organisational resources – for example, the boundaries set by an institution, management, and residency organisation. If we leave it up to the experts, everyone will have slightly different standards. So, it is good to have general guidelines within organisations to avoid situations of different treatment of artists by different residency workers: one might be prepared to answer a resident’s messages in the middle of the night, another one is not. The lack of standards is also frustrating for the residents. When we rely on the rules and boundaries shared by all participants, and understand how they work towards our goal, we as professionals feel more secure. Employees feel supported since they do not need to come up with different rules for every situation and fight for their moral principles. Instead, they rely on formal guidelines.

Resilience comes with knowledge – when I understand why I do what I do, and with training – practice makes perfect.

АK: Psychology often traces the roots of social problems to personal issues, while the reasons behind them actually lie in the imperfections of the system –in this case, the labour system. So it is great to hear you talking about organisational responsibility. I am picking my brain to try and remember if any of the residency managers in Russia ever asked me to work solely during working hours and I cannot think of any. In general, lack of boundaries and overwork are encouraged. You are expected to answer your phone and deal with the issues at any time, at any cost. Managers often adhere to this way of working themselves and expect employees to comply with this unhealthy standard. As for education opportunities in the field of contemporary art, there are, let's say, very few, while education related to working standards and work ethics is virtually non-existent. So on top of not getting any support from the organisation, employees can be asked to leave if they do not want to comply with overwork and lack of boundaries.

From your experience of working with charity organisations and NGOs, would you say that the system is changing? Are there any ways for professionals to network and provide peer support in the absence of support from managers?

ОS: There is not much good news on this front. From time to time, some organisations are keen on using supervision as a way of analysing the practical difficulties that professionals face, but this does not happen regularly. Also, the war has set us back; there is no budget for this.

It is possible to organise meetings for residency workers and to discuss some issues, but it does not prevent people from working the way they are asked to, even if it is harmful. Everyone has their own goals and values. So such meetings can easily turn into a “club of grievances”. Getting emotional support is a good thing, but it is much more efficient to work on relationships with residents and build organisational processes.

It is not that difficult. For example, based on previous interactions with the residents, coordinators can realise that they need to describe their role more clearly next time. It is important for colleagues to share the same standards, because we work as a team. What is a realistic goal for us? Is it to make residents happy at all times? Let's be honest, we cannot do that. Is it to work through all the challenges in their creative processes? No, it is not that. So, what can we do for them in these three months? These questions should primarily be addressed to the manager. However, if the manager delegates some of the decisions to the employees, it is beneficial to discuss these as a team: for example, is it a good idea not to reply to any messages or calls during the weekend?

АK: You mentioned there are two ways to alleviate the stress: education and support. Personally, I do not have a lot of faith in the education system, but how about self-education and self-support?

ОS: When talking about professional stress and burnout, I insist that professionals should not be left alone. Firstly, as you noted in the beginning, people do not always realise that they have ended up in a difficult situation. Due to the nature of the human psyche, this happens in 100% of cases. Usually awareness kicks in when things get really bad. The reason for this lies in cultural features and the fact that we often ignore bodily reactions. However, this cannot be changed as we cannot turn back the time.

I am not completely against self-support. But first and foremost, people need other people with whom they can discuss their situation. One should not only rely on self-help and one’s ability to figure everything out by oneself. Also, developing one’s capacity for reflection makes it possible to become better at noticing when things are starting to take a turn for the worse. However, this is a long process, and it is definitely better to have a safety net in the form of another person.

I am for everyone having a friend or colleague who they are on the same wavelength with. Together, you can educate yourselves by reading books on the topic of burnout and learning that it is associated with a certain kind of stress. If someone starts to stay late at work and ignores their hobbies, it is most likely not caused by the amount of work – they are just starting to burn out. We need to look now for ways to reduce stress and analyse it to better understand the factors behind it. It is great to regularly meet with colleagues and talk about it –this is training for the emotional component of the job. When someone shares the difficulties they face, others can make them more evident and in this way help the person notice these issues and slow down: take an extra day off, delegate, work on stress management.

When thinking about education, the situation is not that straightforward. Actually, I started writing my book because people kept asking me what to read on the topic of burnout, and I could not recommend anything as there was no suitable, practically applicable guide. There are some books for psychologists on interaction with clients, but there is nothing for residency workers on the topic of relationships with residents. One can attempt to extrapolate the knowledge from these, but the problem is that the goals of a psychologist and residency coordinator differ.

АK: I am studying materials on burnout for art workers available in English. There are a number of publications, lectures, and podcasts, but I wouldn’t say that this topic is very developed either. By the way, I came across a statement saying that burnout is associated with the high level of motivation that is typical for those in the art field: where it is far from being profitable, so people are not in it for financial gain. Fortunately, professionals normally do not talk about some higher goal of “serving“ art, but we, perhaps, think about belonging to the important processes of our time and critical knowledge. Is there a connection between motivation and burnout and why?

ОS: The way I see it, this is also about goals. Serving something is an abstract, global, impossible, and immeasurable goal. If this is what you expect from yourself, without trying to break down this goal and seeing what it actually means in practice, you will be ridden with doubts: have I done enough to serve art today? Should I keep serving at night and on vacation? If I do not know what “do a good job“ means, then I have automatically not done enough, and dissatisfaction remains. There is always something: certain things can be done more efficiently, new residents come, and with them – new issues and new challenges. Employees begin to slip: their engines are running at full speed, and they cannot go any faster.

Here, organisation plays a very important role. Let’s imagine a person, bubbling with enthusiasm and ideas, applies for a job. It would be important that the hiring organisation to be clear on the tasks and limits: a working day is eight hours, no overwork, balance between work and rest is important. This way, the organisation sets boundaries. If they are not in place, employees can overwork themselves out of passion for the job they do.

I just had a case where an employee, who works with children with disabilities, started to overwork. This made sense to them, they took on more and more extra hours. At some point, their manager noticed that they were raising their voice at kids, or even grabbing children with hand mobility issues by the arm. The employee sincerely wanted to help these kids, but this is how the desire was expressed. To prevent this from happening, it is necessary to develop standards: what are appropriate ways to help, and what are not. Putting children in a corner, hitting them, and screaming at them is not helping. When there are no restrictions, it is impossible to know what people will turn towards: some go into powerlessness, some into aggression. No matter how driven you are by your mission, you cannot be left alone. Some regulation is needed.

There is another nuance. When people who understand the importance of boundaries come to work for an organisation where it is okay to work during the night, they will either leave rather quickly, or succumb to these standards. The system is much bigger than one person. Once people are in this system, they begin to behave differently because rules and work culture have a strong influence. It can be a good thing: if I tend to overwork, but my manager insists I keep my duties within working hours, I will quickly learn this new habit. But it can as easily go in the other direction: if I want to leave the office at 7.00 pm, but my colleagues are still working with emails and calls pouring in, I will have to either leave the organisation or follow its internal rules.

АK: All of this seems to require experience and training from the management, including setting boundaries and formulating goals.

ОS: When you open a residency, you do not know what is useful and what is not. Some things are agreed upon in advance, and some you will have to figure out as you go. The charity field has developed throughout its history: for example, organisations helping kids in orphanages have developed their support from gifting New Year’s presents to children, to developing courses on social adaptation. At first, gifts were considered as a useful tool, though later it became obvious that occasional support and the constant change of staff do kids more harm than good. Now, there is a clear understanding that kids need opportunities to adapt, learn, and live real lives. This is a classic example, but it is also common in other areas of care work.

Important issues are resolved collectively. After recruiting people, or working together for a season, it is essential to get together with colleagues and discuss what worked well and what did not. Processes can be improved through making conclusions based on the feedback, and a set of core values, goals and objectives will gradually form.

АK: Feedback and discussing results are a must in every cultural project, but this often happens on a very formal basis: slides are shown, the number of residents and events are shared. There seems to be no qualitative evaluation. Here, it is interesting to consider the ultimate goal: residency organisations often aim to develop an area, enrich the cultural life of the “local community“, and attract an audience. For some organisations the residency is a way to build their public programme, for others – to bring new artworks to their collections. However, the resident as a creative unit is barely mentioned in these goals, while the role of the residency worker is neglected altogether. However, supporting, educating, and keeping people sane should also be an important goal.

ОS: Not just that, but also helping them develop as professionals. It is important to remember that developing certain areas and enriching the life of a community cannot be done without people. If the goal is to have more artworks in collections, we are talking about artists. Nothing appears out of thin air, so we should make people want to work for us, and for residents to come back and continue collaborations.

АK: There are people behind everything that happens in an institution.

ОS: I have been thinking about the fact that many famous artists have had some mental health issues. Some artists create their art while being depressed, or while experiencing more severe psychological issues. How do residencies approach this issue? Do they accept artists with mental health issues as residents? What are the standards?

АK: This is a very important topic that remains taboo, at least among Russian residencies. On one hand, people with various mental conditions have the same rights as everyone else and, accordingly, can generally participate in residency open calls. In practice, however, no one really knows how to work with people suffering from mental illness. Sometimes artists do not let residency workers know about their mental health conditions in advance, and a crisis might occur a couple of days after their arrival. This is often left unspoken: one party is afraid of discrimination, while it might simply not have occurred to the other party to ask. If this happens, artists may find themselves in a grey area: exchange of information between residencies happens unofficially, and only a few organizations are ready to take responsibility.

ОS: No wonder why residency coordinators burn out. This, of course, is a very extreme example, but imagine a resident talking about having suicidal thoughts or attempting suicide before – this is very difficult for the residency workers to face. Residency staff is not required to know how to handle, for example, psychosis. But everyone should have instructions on who to call if something happens. This may never occur, but there is always a possibility. So, if there are no instructions on how to handle the situation properly, the lives and health of the residents can be endangered.

When we work with people for a long time and they live at our premises, it is important to learn from such cases, and not sweep them under the rug. It is easy to send a resident home and decide that residents with mental health issues will no longer be eligible for the residency programme. But it would be much more useful to create protocols for emergent situations. This should not be the duty of an employee who has never encountered such issues and does not know how to talk to a person in a difficult situation.

Staff should know fire safety procedures and have first aid skills. Are fires rare? Very. But if they happen and no one knows what to do, it will end in great tragedy. So, the situation here is similar: it is one in a million chance, but if a person commits suicide while in residency, it will have a profound and devastating effect on both artists and residency workers who are unlikely to be able to work well at all, or at least until they have received a lengthy treatment.

This is a huge risk. One needs to rely on the existing experience and think about adequate measures in case something happens. To do this, it is enough to have one or two meetings and develop an algorithm, distribute emergency phone numbers, and be attentive at meetings with artists. If a resident says: “I am going to kill myself“, take it seriously, call a hospital, pass on the information to doctors.

If we are not aware of such algorithms in our everyday life – well, it is a shame. But as professionals, we must know them because we work with people. When it comes to personal relationships, we can decide the level of responsibility we have for other people by ourselves, but at work we must make sure that residents’ life and health are not endangered. If the residents do not warn the staff about their conditions, then the staff’s responsibility is partially diminished. However, residency staff have to be at least minimally prepared.

Having a clear plan alleviates emotional stress. When the staff has all relevant emergency numbers at hand, and they know who to call if someone harms themselves or threatens to hurt others, they can react. Since the situation is outside their area of competence, they do not take full responsibility, instead they share it with medical services. It is of utmost importance to know when the borders of our competences come into contact with someone else’s areas of competence. Even though residency coordinators primarily work with artists, they come into contact with doctors, psychologists, and psychiatrists since residents might find themselves in rather vulnerable situations. It is important to realise this in order to share the responsibility and delegate responsibilities to professionals, if necessary.

The more informed you are, the better the algorithm works. When the numbers of emergency and public services, ambulance, and emergency psychiatric services are at hand, and criteria for reaching out to them is in place, the staff’s responsibility is clear – they can recognise a need and make a call.

АK: In conclusion, I would like to ask what to do and where to start when you feel that you are burnt out?

ОS: I would say that the goal should be not recognising the symptoms, but working to find out what kinds of stress are affecting you and how to reduce or mitigate their impact.

As mentioned, it is worth discussing with your colleagues about which services one needs to call and in what cases – having this information will help the staff feel more confident. It is worth regularly going through what was good, what was bad, what was challenging, and so on. In case extreme situations happen, it is important to give people the opportunity to talk things through and share their emotions, maybe even invite a trained psychologist to attend such meetings.

Five years ago, I would have suggested a client to look for certain symptoms if I suspected a burnout. Now, it is important for me that people do not self-diagnose themselves. In addition to burnout, there are other consequences of excessive professional stress: depression, sub depressive states, panic attacks, anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorders. Self-diagnosing needs to be avoided because some symptoms of burnout can correspond to those of a depressive episode, and treatment plans are different for each case.

If a person starts feeling unwell – if they cry at work on a regular basis, feel severe anxiety, wake up in panic, experiences unwillingness to go to work for more than two weeks, problems with eating and difficulties controlling weight, suffer from regular illnesses, have somatic headaches and other pains that have no physiological explanation –or if illnesses turn chronic, the first thing to do is to book an appointment with a psychologist or psychiatrist, tell about the symptoms, and get diagnosed.

For example, burnout differs from depression in that it is more localised. The symptoms may be similar, but burnout specifically relates to work: a person does not want to go to the office while they want to go out and meet their friends; they are reluctant to do job related tasks, but keep things in order in their own life. There is a fine line: doctors spend years learning differential diagnoses. An average person does not have or know these fine details. However, if someone subjectively feels bad and unable to cope, they need to go and get checked.

АK: “Subjectively“ is an important word here: often we tend not to believe ourselves.

ОS: Let's be honest: the information psychiatrists get from people is subjective, and they rely on it. Psychological and psychiatric diagnostics is based, among other things, on the subjective. A person, of course, may not trust what they feel. However, if I see my colleague crying every day during or after work, I can advise them to go and get help. In other words, I can confirm that what they are going through is not normal. If work causes people so much stress that they cannot sleep, or need to get through a bottle of wine to fall asleep at night, this is not normal. We can verify this, but then it is up to a person to go and get help.

One more thing – one efficient way to prevent burnout is compliance with the Labour Code. It states quite clearly that weekends and vacations have to be provided, the working hours must be specified in the contract, and the overwork hours should be paid for. Then managers can decide if they want to ask people to work extra hours and pay double for it. This helps to be more realistic rather than talking about motivation and serving some higher purpose. Let's come back to earth and look at the regulations that are in place. The Labour Code of the Russian Federation is not ideal and, probably not exhaustive, but often even basic labour rights are ignored. Once the code of basic rights is followed, employees will feel better.