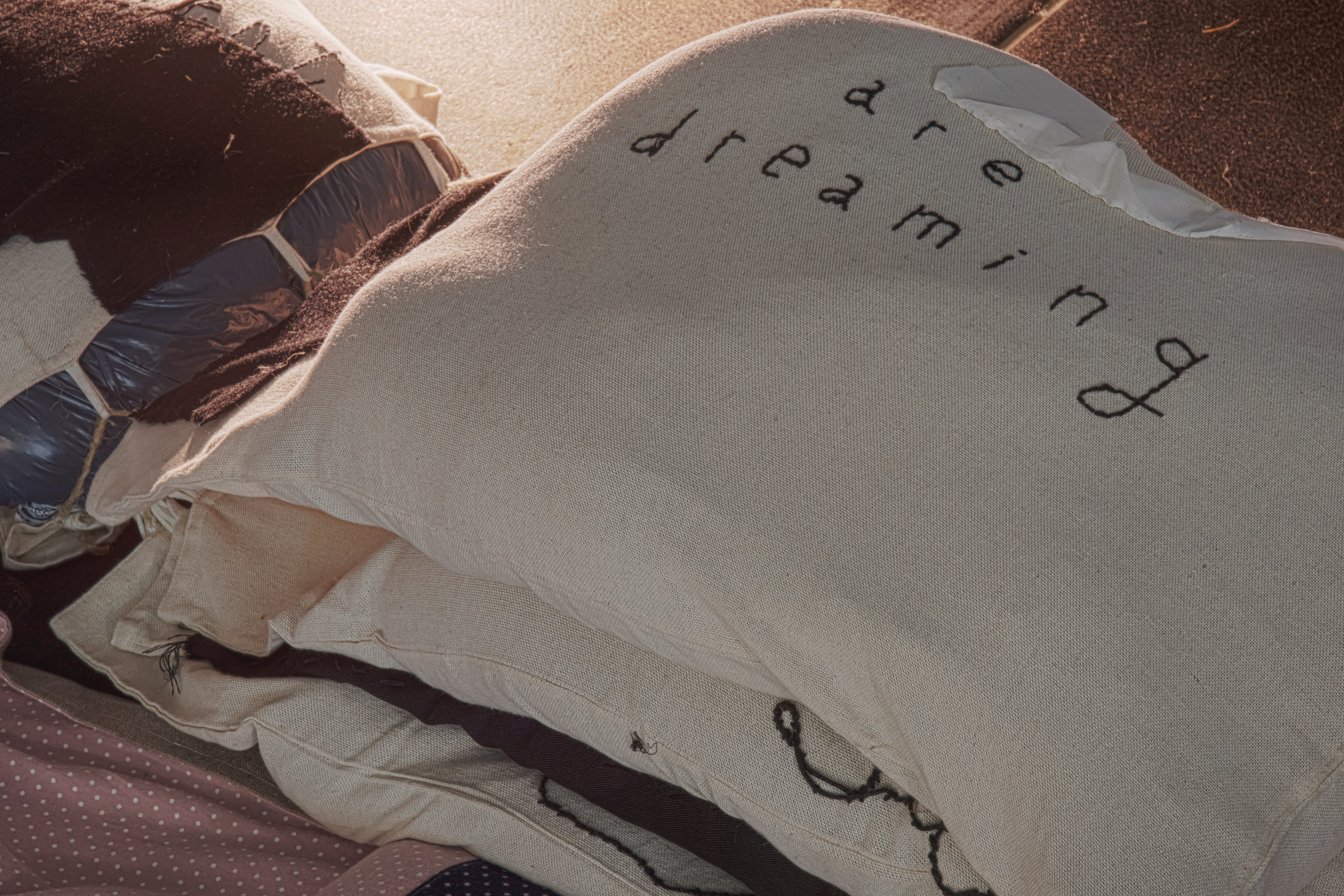

Cover image: Invasion by Katerina Verba, 2023

Photo: Tanya Sushenkova

Cover image: Invasion by Katerina Verba, 2023

Photo: Tanya Sushenkova

Discussion on environmental issues is becoming increasingly common for contemporary art projects in Russia. Alongside conceptual and aesthetic aspects, it touches upon practical and production-related issues of artistic and exhibition activities.

Last summer, the Center for Creative Industries Fabrika (Moscow) hosted an exhibition based on the results of a laboratory devoted to a study of invisible cycles in urban nature. In this text, exhibition curator Christina Pestova, and consulting biologist Elena Shelyagina, talk about the idea behind the project and its implementation, while artists Katerina Verba, Anna Komarova, Sofia Sapozhnikova, and Elena Sokolova reflect on their experience of a dialogue and collaboration at the intersection of disciplines, and voice out questions that arose during their work on the exhibition.

The Center for Creative Industries Fabrika (also known as CCI Fabrika) is one of the first art clusters in Russia which opened in 2005. It operates at the venue of a former Soviet technical paper factory. CCI Fabrika's goal is to bring together manufacturing and creative (artistic) labour. It is home to artist studios, creative workshops, residencies, exhibition spaces, community programmes, and production units working with creative industries. CCI Fabrika has managed to create a unique space that supports experimental non-profit art projects and their creators, in Moscow.

Moscow Circular conducts research, and works towards the popularisation and implementation of circular economy principles in Russia. In circular economy, all production, consumption, and economic relations are reconsidered by making more rational use of resources, goods, and materials by preserving their value, and enriching natural systems. Among other things, Moscow Circular works with art and culture, collaborating with artists and creative industries to rethink existing systems and inspire people to work towards change.

Christina Pestova, curator: In the summer of 2023, CCI Fabrika, together with the Moscow Circular team, launched a laboratory for artists named “Invisible natural cycles in the city.” In the past, we had attempted to create a stable platform for the exchange of ideas and practices among urban eco-initiatives. However, it always followed an activist, spontaneous approach to working with a place, and while topics of longevity and sustainability surfaced from time to time, they eventually faded into the background.

In 2016, CCI Fabrika hosted the International Green Documentary Film Festival ECOCUP that brought together directors and environmental activists from the USA, Italy, Finland, the Philippines, Germany, and Serbia. The activist environment, being part of CCI Fabrika community in one way or another, developed eco-interventions and public eco-projects: an urban garden and the community project “Sincere Seeding” by artist Dima Green, in 2019, are some examples. In times of acute despair and turbulence, CCI Fabrika invited artists to plant flowers and grow vegetables on its territory, seeing it more as a therapeutic practice rather than a contribution to the development of sustainability on behalf of cultural institutions. However, the results of this experience did not last.

This laboratory was essential in beginning a transition away from a theoretical process of “imagining nature” and reproducing speculative ecologism. Keeping this in mind, the laboratory was also educational and dialogical in nature. Conversations with biologist, consultant, and researcher Lena Shelyagina helped participants to better understand natural processes, while formulating and teaching the language of urban nature.

Over the course of three months, artists involved in the project had the opportunity to learn this new language and to interpret semantic structures created by living environments. The results of the laboratory were materialised in artworks and installations: “Invasion” by Katerina Verba touched on the violation of biodiversity in the urban environment caused by landscape design; Anna Komarova’s “Secret Garden” contemplated the problem of overuse and on how control is shifted from natural processes to industry conditions, embodying the concept it in the image of the Soviet greenhouse familiar and dear to many; the installation “Lullaby” by Sofia Sapozhnikova explored the relationship between humans and soil, allowing the audience to feel the heaviness of the earth and its therapeutic qualities; while Elena Sokolova's paired work “House for Insects” and “Loss” emphasised the aesthetics of non-human agents' (insects) logic and our inability to access, comprehend and reproduce it. In this text, we would like to focus on the questions that were raised over the course of the laboratory workshop.

The questions involve issues of environmentally friendly production and the (dis)installation of exhibition projects in cultural institutions, including the ethics of relationships between human and non-human agents, responsibility, and our relationship with those on behalf of whom we speak and who are featured in our works without their direct consent; eco-utopias that are intended to highlight problems, but can be seen as a manipulative strategy by the viewers. Where does the line between the responsibility of the artists, and the responsibility of the institutions lie? Can we radically rethink artistic aesthetics in works in order to move away from reproducing essentialist images of nature? How can we make sense of the multiple ecologies that we have created?

Lena Shelyagina, Biologist: A gap between the “original'' structure of nature and the development of human civilisation drew the attention of researchers and thinkers long before the 20th century. With the release of the Club of Rome report “The Limits to Growth” in 1972, clearly highlighting the limits of world economic growth, it became obvious that environmental issues affect all of us. Since then, conversations about the destruction of natural systems and their consequences have become more profound; they now include the perspectives of scientists, activists, and journalists, and influence management level decisions. However, this does not seem to be enough – we need to go back to the starting point of how we perceive natural systems, to understand their vital functions, and reconsider what place humans hold as an element in the bigger system, not as a highly developed superstructure above it. It was a joyful and exciting experience for me to combine academic knowledge about the structure of the biosphere with the artistic views of the laboratory participants, and to dive into the study of the “original structure”, and the “alignment of forces”.

We agreed that natural, urban systems were going to be the theme for the laboratory – often invisible, always at work, changing under the conditions of urban development, but at the same time determining their existence. Who are they, the invisible inhabitants of the city, what processes remain invisible to us? Can we go back to a peaceful and non-destructive coexistence with natural systems?

We used the first month of the laboratory to immerse ourselves in the theory of natural cycles and urban biodiversity. The educational part included four lectures: “Natural systems and natural cycles”, “Water in the city: from drops to reservoirs”, “Soil in the city: the underground world” and “Invisible city inhabitants: who are they?” Starting with the structure of planetary systems, we went through the spiral of knowledge from natural cycles in the city, to individual elements of biodiversity. We concluded the educational part with a walk through a city park in Moscow, where we examined, touched, and found traces of those city inhabitants that usually remain hidden from our eyes. After this, the artists began their work.

Biodiversity and artistic practices

Anna Komarova, Artist: “Invisible natural cycles in the city” – the title itself refers to aspects that are invisible, hidden in the depths, not to the superficial issues of relationships between humans and nature.

Thinking about ecology, the first things that come to mind are global warming and waste sorting. It seems to be enough to put garbage into a container with the right label on it, to solve all problems and make the world clean and beautiful. A blue container for recycling, a black one for landfill. Are there any other problems apart from waste and rising temperatures?

Small particles hidden in soil, water, and air are all interconnected and affect the problems that are visible on the surface. Natural cycles are a global phenomenon. They include water cycles, the change of seasons, and the life cycle of a dandelion or locust. When these cycles are interrupted, even on the level of insects, it affects other species, and as a result, the entire planet Earth. The human desire to force these cycles or their parts into submission. The very attempt to control them, causes them to change and readjust, and in some cases even disappear.

It is as if the “butterfly effect” would apply not only to time, but to space.

It is worth looking at influences beyond extremes such as the clearcutting of an entire forest. Poultry farms control the lives of chickens, dams change the course of rivers, honey apiaries and tea plantations, vegetable gardens grown to attract some insects and deprive others of food – these are small particles that make up the whole.

There are fewer wild bees. Are there less meadows as a result?

Today is the 29th of January. I’m eating a red apple, where did it come from?

Sofya Sapozhnikova, Artist: I explore the regularities and rhythms that organise human life – in social environments and in nature – including their influence on each other: natural cycles, seasonal and social changes, as well as the rituals that accompany them. When I turned to the topic of natural systems, I hoped to expand the context for studying these processes. By focusing on green spaces, topography, soils and waters that shape urban biodiversity, I noticed more and more actors that participate in processes that repeat from season to season. I study the phenomenon of life that unites these processes, and its finitude, which is also a unifying factor.

Immersing myself in the topic of biodiversity gave me a reason to move from graphics, to working with the environment. Instead of illustrating natural cycles, I gave viewers the opportunity to physically feel them, in the installation I created for the exhibition «Boundaries of the invisible».

It was important for me to create a space for perceptual interaction with the exhibition, a place that enabled a transition from verbal and visual information. This is how “Lullaby” appeared – an installation where viewers sat, lay down, talked, had a bite to eat, and covered themselves with an earth-filled blanket that weighed around 180 kg.

Elena Sokolova, Artist: My work “Loss” talks about the fragility of biodiversity. Insects eating alder buckthorn turned the leaves into a sort of green lace. This has its own aesthetic, but holds a great sadness at the same time: this forest lace tells the story of a forest that, due to the loss of biodiversity, has become unstable and vulnerable to pests.

I have observed this forest for the past 10 years. It is an attempt at artificial reforestation by pine monoculture. When I first came across it, it was no more than 20 years old. The trees were planted very close to each other and they became tall and thin as a result, competing for light. After six years, they began to break and fall from the snow and winds during winter time. Three years later, I noticed that the young alder buckthorn undergrowth was entirely eaten by insects throughout a large territory. I realised that it was not the wind that destroyed the pine trees, but bark beetles. Because of them, pines dry out, making it easier for the wind to break them. Therefore, this green lace of leaves is a consequence of monoculture forestation, the result of an ill-conceived human attempt to control natural processes.

In the city, this control becomes more decisive – it seems that natural urban systems are intended to be unlike natural ones. As a result of the deliberate replacement of local biodiversity by planting monocultures of non-native species, urban forests and parks become even more fragile and vulnerable, serving the aesthetic and engineering goals of the city, while people become even more alienated from natural ecosystems.

Ecological anti-utopia and loss of contact with natural systems

Anna Komarova, Artist: Invisible problems pile up, and invisible cycles deviate.

Today I walked down the street, it was very warm outside. There was a twenty degree difference between the temperatures of yesterday and today. This happens continually – where do these fluctuations come from?

Maybe it is the salt that is used to remove the snow? The snow melts and flows into overflowing drains in black rivers, continuing its journey further on. Probably, these black streams end up in bodies of water that are “unsuitable for humans.” Or maybe they end up in the soil. This black water flows in the radiators – however, it does not seem to come from the streets. Why is it black?

I once visited Karabash. It is a city in the Chelyabinsk region famous for its black hills entirely made up of industrial waste. Karabash is known for its scorched earth -- as if a piece of Mars fell off and landed right there.

Gasoline puddles and an acrid sour smell are stuck in my memory.

The artist Olafur Eliasson once dyed a river bright green to draw attention to environmental problems. He claimed it was completely harmless. However, when European activists performed the same trick, dead fish appeared on the surface of the river, bellies up.

There are a lot of artists working with the topic of ecology. However, I always wonder if any of their works were successful in drawing attention to a problem, and offering a solution for it; that it had had such a profound impact that it had inspired action?

Upcycling seems to be the smartest way to produce art on this topic.

Black water from drains and black water from radiators – no one dyed it, but it frightens, fascinates, and attracts attention.

Perhaps if this is turned into an artwork, it might facilitate change?

Sofia Sapozhnikova, Artist: In the study of biological processes, I am especially interested in normalising the perception of death, taking it back it to its rightful place (I keep the memory of a custom I witnessed in the Balkans -- there, weekly announcements about deceased citizens were placed on special information boards for the public to see).

I observe how the idea of mortality is banished to the periphery in the developing metropolis. Something new is immediately created to replace the old. For me, gathering fallen leaves and disposing of them is another practice of eliminating death from the natural cycle. During the laboratory that preceded the exhibition, biologist Lena Shelyagina talked about how in the wild, a rotten tree is incorporated into the forest system in a new capacity. It decays slowly, providing shelter for many insects.

I value the thanatological meanings that arise in the installation. I believe that the experience of coexisting with entropy is no less important than the willful resistance to it.

I created my artwork – the heavy blanket – in collaboration with artist and engineer Galina Morozova. It is rectangular in shape, about 300x300 cm in size, made from baize and sackcloth. Inside, there are bags of garden soil. Medical simulators used in therapeutic purposes for dealing with anxiety and high muscle tone, acted as reference for the artwork.

I encountered similar devices while working in a workshop for teenagers on the autism spectrum. There, interaction often happened on a non-verbal level. Cooking together, playing ball, doing ceramics, painting, and playing music had therapeutic effects – an important lesson on how the body and the mind perform in unison. I would like to thank my colleagues Margarita Polisskaya, Tatyana Eskova and many others for this precious experience of working together.

An important part of my installation was the dim lighting and monotonous soundtrack based on a lullaby constantly playing from either an eerie music box or a baby crib mobile. To cover members of the audience with this soil blanket, I needed help from other exhibition visitors. The blanket, this almost impossible-to-lift object, creates conditions for joint action. The ritual nature of the process immerses participants in a shared bodily experience. Being covered with soil is the moment in which we accept the care of others, and come together.

Eco-ethics

Katerina Verba, Artist: “Is it ethical to use live plants in an exhibition?” I have heard this question more than once. However, I often ask myself a slightly different question: “Is it ethical to use ANYTHING in an exhibition?” Plants die so we can have paper, the production of paint harms the environment, construction of plasterboard walls for the sake of one exhibition often makes no sense – these things worry me more. In all my projects, I stick to the rule of avoiding unnecessary waste, leaving only a cultural trace. Therefore, I have always been interested in creating artworks that are completely biodegradable -- so far I have achieved this goal at 80-90%. Using plants seems natural to me. I am sure that nothing in nature wants to die for nothing, and the death of any living organism has a purpose -- this is how natural cycles work. Serving art is also an important purpose, I think. In this case, one has to consider where the plants come from and where they will go after the exhibition. Many office gardens, for example, are created by «adopting» plants used in exhibitions.

I needed meadow plants for the project at CCI Fabrika. I dug some up at the construction site of a private house in Crimea, where an excavator was digging a road; the soil mottled with plant roots looked like a slice of layer cake. I rescued some plants that are generally considered “weeds” from a garden in the Krasnodar Territory -- they were in danger of being pulled out anyway. Other plants came from the construction site of a new residential complex in the Tsaritsyno district of Moscow. When I was digging up chamomiles from a pit in front of the construction site, workers came to tell me where I could find more – it was very touching. The most surprising thing was that the plants that were included in the exhibition outlived their counterparts – in less than a month, the foundation pit was filled in, while the flowers I took from there were still blooming as part of the installation.

Lena Shelyagina, Biologist: Working with living plants for the installation seemed to expand the boundaries of the artwork in both time and space. At first, parts of the installation lived and grew separately in different cities, being later brought together under the roof of CCI Fabrika, to continue their development within the framework of the exhibition. The question of what to do with the plants became more urgent after the exhibition closed – it was impossible to pick up a flowering meadow, put it in a bag, and toss it into the dumpster. Living plants gained power and took over the initiative communicating their demands to the artist. As a result, we found a way for each of the exhibition’s elements to continue living outside the CCI Fabrika space – as soil in a flower pot, flower bed on someone’s balcony, or as mulch. The installation breaks down into elements that find a new place in the system, continuing to support their development or the development of other organisms. Just as it occurs in nature.

Elena Sokolova, Artist: What is the connection and distance between the conceptual, aesthetic, and declarative part of an art project, and its production or implementation? For me, these things are closely connected. It is not about equality of form and substance. I am interested in other questions: should the production of an art project on the topic of eco-agenda be environmentally friendly? Can we really cause no harm? In other words, is it acceptable to act in an unsustainable way in order to create a project that draws attention to the issues of climate change, biodiversity loss, and the consumerism attitude towards nature? What damage do we cause in the name of saving nature? Does an art project devoted to the eco-agenda contain self-negation if considered from a production point of view? How important is the method with which something is done Vs. what is done? What happens to the project after the exhibition ends? Destroying nature for the sake of making a project about ecocide is a strategy similar to “bombing for peace.” Isn’t the artist working with an eco-agenda exploiting both the topic and nature doubly?

I'm interested in analysing these questions through the notion of biopower. Humans as a species, exercise this power in relation to nature as a whole. Artists endow themselves with power in their creative work, and with biopower when they exploit nature for their projects. Exercising biopower, in this context, means the implementation of artistic work in a way that leads to destruction of a small or large element of living nature, or to consequentially interfere with it.

This interference can affect both a single living organism as well as a group of organisms (part of a specific ecosystem) or habitat (part of a biotope). The way I see it, we should not be talking about individual elements, but rather about the biosphere and habitats as a whole, since ending life or causing harm is always a matter of choice. Artists make the decision to let something live, to cause harm, or to interfere with the life of a living organism: pick a flower, catch wild fish, cut down a tree or move hundreds of tons of soil. It's a question of scale, not fact/reality.

How can artists become aware of the manifestations of biopower in relation to nature? How to find the balance when granting yourself the right to exercise biopower?

What is the environmental cost of producing an artwork?

Does the way an artwork is produced, influence its meaning and the viewer's perception of it?

Final words

Lena Shelyagina, Biologist: It was surprising and extremely valuable that the artists managed to touch on multiple aspects of urban biodiversity. In one small exhibition, we were able to show the fascinating “morbid history” of the city – the transformed soils and meadows, the lichens and insects inadvertently excluded from urban life, and the frightening development of technocratic attitude towards the source of all life. At the same time, we succeeded in exploring not just different layers of space, but also time. The exhibition acts as a return to the past, a careful account of the present, and a reflection for a possible future.

Christina Pestova, Curator: Looking back and analysing the experience of our “invisible” laboratory, I think that the viscous, contemplative format we chose, worked perfectly for us. The artists created works and displayed them in a way that finalised the project, summing up conducted intellectual and artistic work. At the same time, the process of setting up the exhibition and contemplating what was created, gave impetus to rethinking the well-established formats of representation and perhaps sowed, in us, the seeds of uncertainty.

What did we do when we brought these fragile and ever-changing natural agents into the industrial space of CCI Fabrika? How did we experience being inclusive of the existing Other, what did we learn and how did we communicate our understanding? I will ask one more question as the representative of the institution: could we have avoided production logic and, if so, how far can we go in planning such a laboratory? What is the role of institutions when the landscape around us no longer supports the emergence of activist gestures, experiments, and claims to action in the broad field of the public and urban? By vocalising these “Boundaries of the Invisible'', we attempted to document the present and our attitudes towards the living, and ultimately, gave ourselves the opportunity to be uncertain.