Text and photos: Angelina Davydova

THE END OF THE PREVIOUS NORMAL

”I believe that you can talk about both the terrible things we should engage with and the losses behind us, as well as the wins and achievements that give us confidence to endeavour to keep pursuing the possibilities. I write to give aid and comfort to people who feel overwhelmed by the defeatist perspective, to encourage people to stand up and participate, to look forward at what we can do and back at what we have done.”

Rebecca Solnit, “Hope in the Dark”

I wrote this text in mid-November, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, at the UN climate conference. For many years I have been participating in the conference as an observer, and recounting what is happening in global climate policy to a Russian and international audience. This year's climate summit was somewhat special for me. In March 2022, I decided to leave Russia (only temporarily, I hope) so this year I participated in the climate conference in a new capacity — as a journalist and observer based in Berlin, but still focusing on everything climate related in Russia and other countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

But even in Egypt, observing the UN-level, international climate negotiations, I could not completely ignore what was (and still is) happening in Ukraine and Russia. This text is, for the most part, a reflection on my experience at the COP27, while the war continues in Ukraine, and I am watching something in Russia, that I can only refer to as the collapse of my world.

I have been participating in UN climate conferences (COP27) for a while. This year, the event took place in Egypt, where the political situation, honestly speaking, is challenging. In the history of UN climate summits, I don’t remember having experienced this degree of control, explicit and implicit surveillance, or bans on free speech and action. In cafes, people would come and sit down at the tables next to my fellow negotiation observers, and record their conversations almost openly. Upon being exposed, they would apologise and leave. According to different estimates, tens of thousands of people in Egypt were imprisoned for political reasons — however, in the months before COP27, the authorities released several dozen of them. One of those still imprisoned is Alaa Abd El-Fattah, a British-Egyptian activist who had started a hunger strike many months ago, and went on a dry hunger strike the day the COP27 began. (It now seems that he has stopped them both.) His sister spoke at the conference here, at an event organised by Amnesty International. The Egyptian authorities actively opposed this and officially expressed their criticism. At some events, whenever the topic was brought up in one way or another, the Egyptian participants who introduced themselves as researchers or such, would stand up and say "Why do you, Western people, teach us about life?" Naomi Klein wrote an article "Greenwashing a police state: the truth behind Egypt's COP27 masquerade". It obviously reminded me of something. This is the first point I wanted to share.

Now comes the second. Since the beginning of the war, I have not written anything about my emotional state or about the difficulties related to the practical side of relocating to another country. I thought to myself "Who from my circle of close and distant friends would be interested in this? Everyone is going through a hard time now". I cried on the shoulders of those close to me, sometimes I reached out to those who were far away. And sadly, there is less and less time and energy to maintain distant connections.

In the past month and a half, I have been to Tbilisi, Istanbul, Almaty, Vilnius, Paris, and now I am in Sharm el-Sheikh. In all of these places I saw several dozen close friends and colleagues who have; left Russia permanently, left for a while or just left to participate in an event. I will write a separate, detailed article about this, but for now I want to say one thing. I realised that my social and, in many respects, professional circle was torn apart, broken, dispersed. All of our conversations are warm and wonderful, but almost everyone feels lost, some still do not believe that this will last, some no longer know what to believe in. There are exceptions — a few friends suddenly decided that it is high time to do whatever you want, what you have always dreamed of. For example Dmitriy Marinskikh, a good friend of mine, is currently riding his bicycle through a third country already.

I cannot do this yet.

The very fact that I met and talked to so many dear people knocked me down emotionally and brought me close to what I experienced in April this year. In parallel, I suddenly realised that I have a heightened perception of things that are wrong, unfair, evil, and cruel. As if the scales have fallen from my eyes, isn't that the expression? And what about before, was I seeing through dark glasses?

Although my sight has literally become poorer.

I understand that here I am, a person who was born in the USSR, on the ground floor of a Khrushchev building on the outskirts of Leningrad, in an area that hosted the most famous drug market in the 1990s. A person incorrectly diagnosed in childhood with a disability that was easier to "leave behind" at some point, like some sort of stigma, and to make life more convenient by obtaining new medical papers in order to enter a university that was considered "prestigious", and to not be "different" or "othered" in any way. My grandfather was in the Gulag (Translator's note: system of forced labour camps) twice during his youth for stealing a couple of potatoes from the Kazakh fields during the evacuation from Leningrad. His favourite author in the last years of his life was Varlam Shalamov (Translator’s note: Varlam Shalamov was a Russian writer, journalist, and Gulag survivor. Some of his most well-known works include Kolyma tales – collection of short stories about his experiences in the labour camps). In the 1980s my father (an engineer, like many others in the USSR) was never able to find meaning in life, started drinking heavily in the 1990s, and died at the age of 44 (the same age I am now). I did not see him after the age of two.

I could not and did not want to read, discuss, or listen to any of this. For me, that reality was too bitter. Through many internal changes, by virtue of external luck, and probably a bit of something else, I created a different reality for myself. A reality that was interesting to explore with open eyes, to learn new things, talk about it, think about the future, help others, and discover the world – for myself and others.

"Climate" in many ways has become a topic and channel into the future for me. "Climate" as the path to a future that is more environmentally friendly, socially fair, humane and kind, with regards to relationships between people, as well as between people, animals, and other inhabitants of this planet.

We thought and discussed (and we continue doing so) new economic models, systems for natural resources management (or for leaving the natural resources alone, untouched). We discussed systems for building a common life on the planet by people from different countries, even though the very existence of states, borders, and power elites already seems outdated and unnecessary – this ponderously authoritative and bureaucratic atavism. We tried looking beyond the horizon, creating models and scenarios of what we wanted to see, where dreams were fulfilled, and decisions were made by some new public decision making structures, local communities? Groups of people who agree on things, and citizens of something new, perhaps global?

Now I have the feeling that I see all the injustice, all the hopelessness and lack of future in the world – something I once consciously moved away from. This whole gloomy (and by no means new) picture of what is happening in various regions of the world: Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, and many other countries – paints a picture of despair and powerlessness. Where is the future that I would like to see? Where is the future that I hoped for, for me and many other people, many of those who have now left the country and the city where I grew up in, the place we worked together to create? Has everything that I have done lost its value and meaning? These are the questions I asked myself in April. And I keep asking them now.

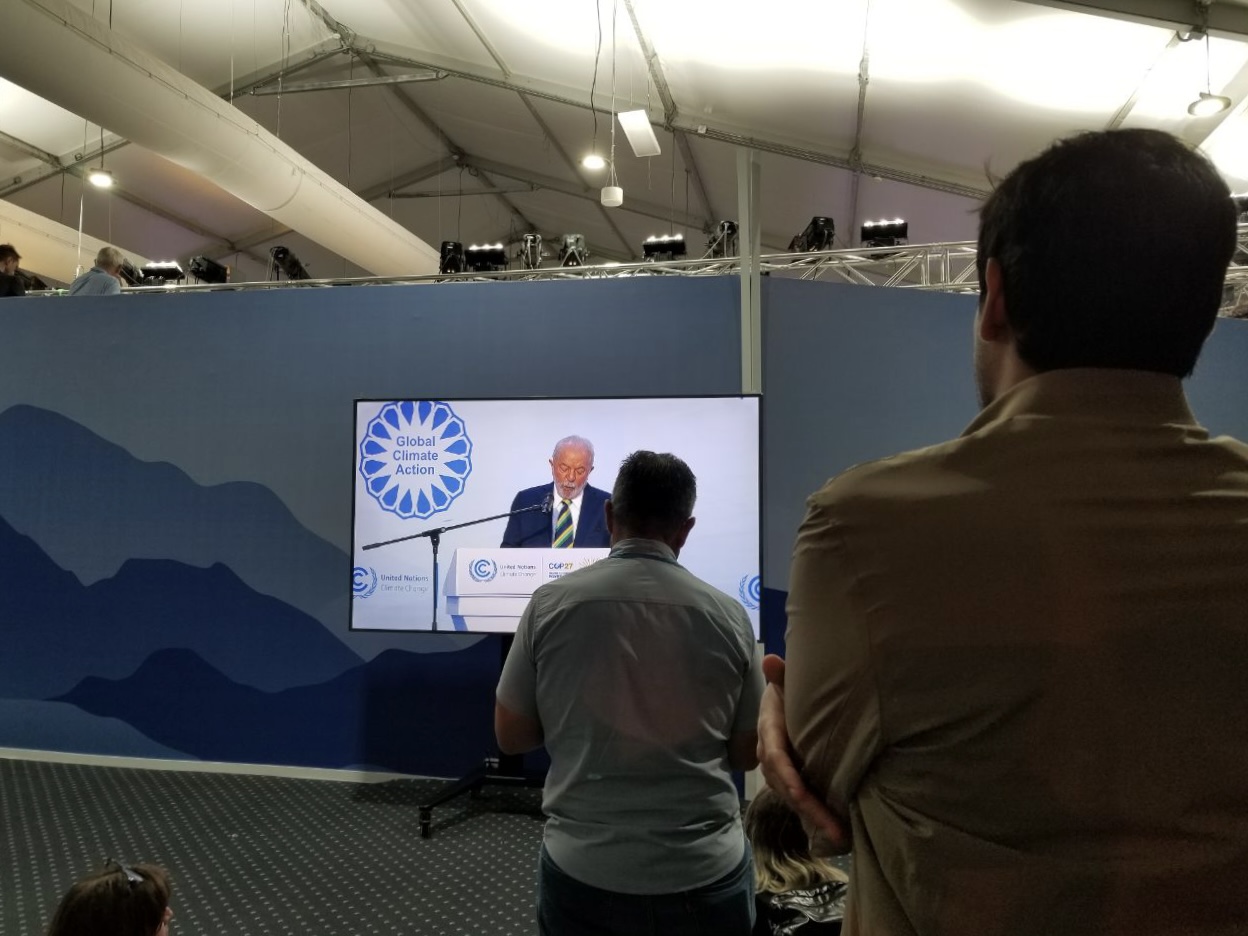

The third point. The newly elected president of Brazil, Lula, spoke in the second week of the COP27. The organisers failed again to translate the speech properly, so I did not immediately understand the message, but I read about what was discussed later. I know that public politics is about strong statements, public figures, and the image that a team of people is working on. At the UN climate conferences, for example, John Kerry is this kind of informal climate celebrity. I understand that Lula can be criticised for many things — including the enormity of corruption in the country during his previous terms of presidency. However, on that day at the COP27 he looked like a real "people's" politician – regardless of how we feel about this word. A politician who is not perfect, makes mistakes, is subject to influence, provokes criticism and debate — but who represents many people in their country and strives for positive change based on the perspective of his voters.

Brazil had three pavilions at the COP27: the official national pavilion, one from the Amazon region, and one from civil society. Civil society has, and rightfully so, a position which differs from that of the official national position. It is cause for dispute, discussions, and debates over right or wrong decisions, but not for lawsuits, persecution or imprisonment. At the COP27 I spoke with many Brazilian journalists and activists. I know very little about Brazil. I have been there only twice, and then tried to learn the language two times, before more pressing matters took me to other countries and regions of the world.

Everyone close to me remembers how I became interested in Brazil, and how astounded I was by my discussions with many former oppositional leaders (now in their 60s and 70s) who had left their country during the dictatorship period. Most of them lived in Paris, and after 10-15 years, as opportunities emerged (as first, the regime softened, and then changed) returned to their country. All of them said it was the greatest and happiest event of their lives. There were hundreds (thousands?) of people. I do not know many of them. I only spoke to a few. Which is why I am writing this text, and not a journalistic article. In April, when I was interviewed for a German documentary film, I remembered these people and burst into tears. At the COP27 I left the pavilion where Lula spoke, grabbed a cup of coffee, sat down under the dark, starry Egyptian sky on a warm November evening and could not explain all these complex feelings that had surfaced in me over the past hour. That is why I wrote this. Do we have the time to wait for 10, 15, 30 years? What can we do now? Where is the image of the future I want to see?

I understand that many people close to me are also discussing these issues right now.

The war continues, people are dying, cities are being destroyed, the citizens of my country execute people in front of the camera. I experience this as a collapse of my civilization and my world, as a former colleague of mine, Mikhail Korostikov, wrote earlier on Facebook.

But I want to see the future.

P.S. I thought that I should also mention something else. A few weeks ago, a friend invited me to the taz Panter Preis award ceremony in Berlin.

The award is for solidary and socially just solutions for climate crises (in Germany, but not exclusively). These solutions are often very local and small scale, but they enable important social changes. The main prize went to an activist from Nigeria who has been living in Berlin for many years. He has protested and continues to protest against the pollution caused by international oil companies, primarily Shell, in his home country. Twenty-seven years ago, many of his fellow protesters were murdered.

It is hard to compare that kind of experience with anything else, so I think this is why the jury chose to give the most prestigious award to this project. But I also feel it is important to talk about the other projects: for example, the years-long protest of local villagers against open cast coal mining in the Rhine Valley, including an ongoing protest action with a camp.

Aerial photographs showed exactly what the open cast mining area looks like, terraformation that literally changes the fabric of the Earth, and shows us that the Anthropocene is already here and now. And it tells us: some groups of people and companies are already altering the surface of the planet and interfering with ecosystems. The impact of their activities is more severe than the damage caused by any other factor on Earth.

And then there were other projects as well – a supermarket working as a farmers’ cooperative in a socially lower class neighbourhood of Berlin, selling farm products directly from producers at affordable prices.

Another example was a civil society initiative that buys plots of agricultural land and only leases them to farmers who practise sustainable regenerative agriculture that helps to maintain the health of the soil.

You can read more about the projects here.

Having attended the award ceremony, I was preoccupied by the thought that in recent years, some similar initiatives have been attempted in Russia. I feel like a lot of my professional mission has been to support these activists and to help them in all possible ways; to talk about them publicly, to introduce them to potential international partners and to get them connected to the world on a global scale. I wanted to help them grow, from something small-scale to something important, something which has an impact. Sometimes simply by encouraging them with "Come on, you can do it."

But then some of these projects and initiatives, and many protest actions and campaigns, have not always worked out in Russia. They have often experienced (and are still experiencing) immense physical, legal, and financial pressure. It now feels so heart-breaking that people cannot accomplish their ideas, fight for what they consider necessary and important, or go out to a protest action without being afraid.

It now looks completely different, especially from this perspective, or rather, this perspective of a cancelled future.

I am thinking of what else I can do now.