Text: Angelina Davydova

Photo: Jaana Denisova

Text: Angelina Davydova

Photo: Jaana Denisova

This trip West of Helsinki takes us from early morning until late in the evening. It’s a sunny day, and after the snowy hills of Mustarinda it looks as if we have travelled not only southward, but also in time, from the early waking spring into the baby summer with its loud sunlight that one tans in easily, and the delicate buds all over the trees and bushes as well as the sprawling thin grass one is afraid to step on.

Residencies as living networks

The first residency where we sit down for coffee and tea, is the home residency of Meri Linna. During the Corona pandemic she bought a two-storied house (which used to be a meat/dairy shop) at the intersection of the two roads near Raasepori.

The house was built by Sigurd Frosterus, the same architect who designed the Stockmann building in Helsinki. It stands on a reclining hill, overlooking the road and the trees on one side, and the river and other trees on the other side. Both floors have street level exits, making a surprising twist in our heads as we go up and down.

Meri is still in the process of rebuilding the house, and it will take her a while. She installed a heat pump which allows for energy-efficient heating of the house, she is painting the walls white for the residency rooms on the ground floor, and she has set up almost a dozen diverse “houses” for her cat Vincent all over the place.

Meri Linna is an artist who has been working with the topic of human residue for many years, collecting human urine and faeces and transforming them into art objects. In the basement she has a collection of urines from various people from over many years – all in huge jars stored on wooden shelves. They’re waiting to be transformed into art.

Meri also mentions how once at midday, she saw a ghost – a woman smoking on the bridge over the river. The woman disappeared after a while, but Meri has been on the watch ever since.

The area is very quiet otherwise.

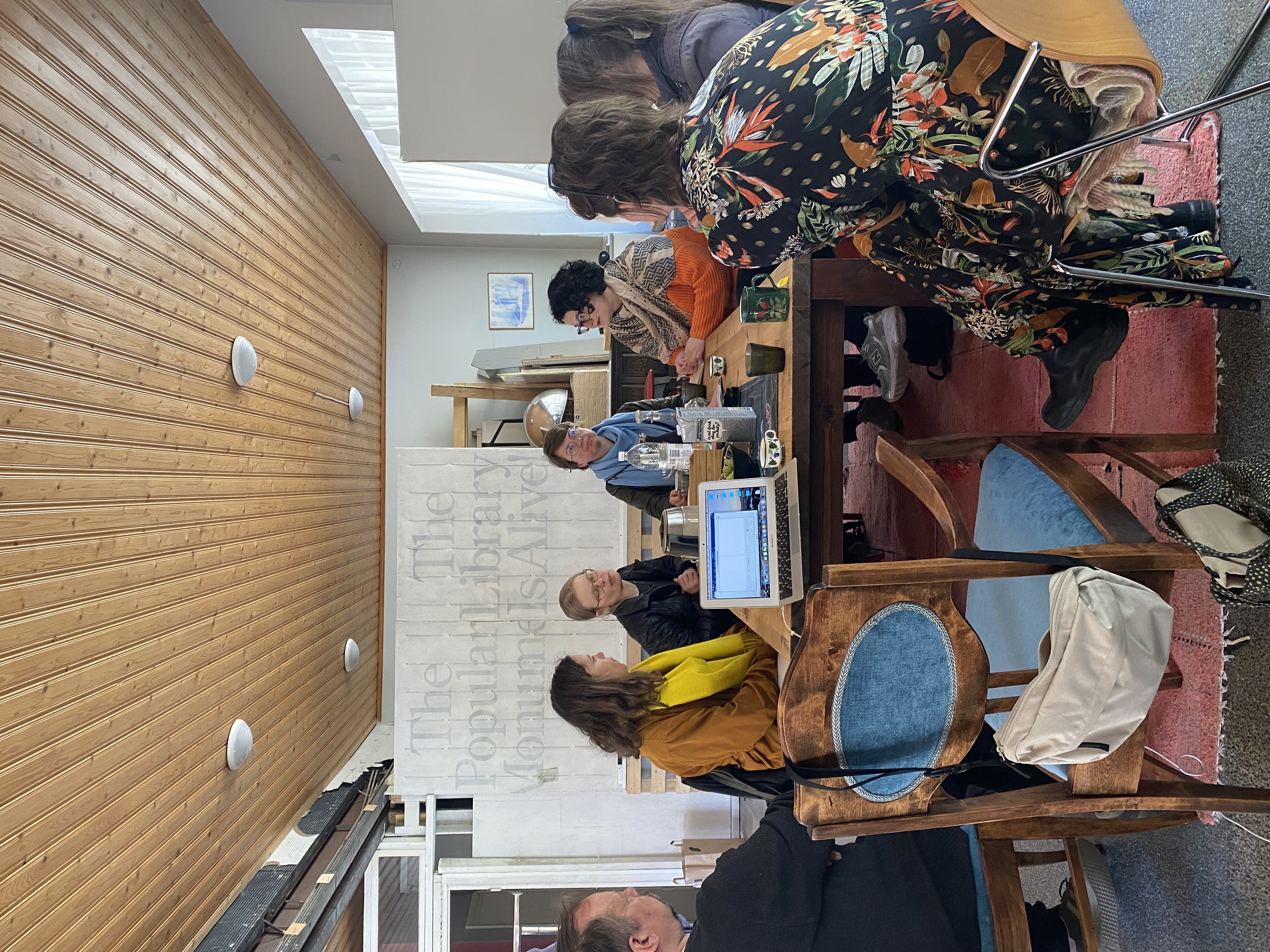

Also, together with our team, in her house are; the artist Perttu Saksa, who is currently setting up a residency for writers, artists and researchers not far from Meri Linna’s house, curator Ki Nurmenniemi, artist Dafna Maimon, and the creator of the Värtsilä Art Residency, Karoliina Arvilommi. We speak about what sustainability means these days – both in general and for art residencies in particular. Apart from climate-friendly and resource-efficient practices, we also talk about how important human and institutional relationships are, including their networks and collaborative patterns.

“Residencies connect the personal and professional, that is why they are so important in terms of sustainability. Private residencies could reach out to larger institutions and show them ways to work differently”, Meri Linna says. She calls it an ‘anglerfish approach’ which implies becoming part of a bigger institution or initiative, while still providing something vital of their own.

“Sustainability is also about combining resources instead of doing everything on your own. Stepping away from individualism and doing something together”, Meri continues. She also speaks about the importance of building a network of private residencies, so that people can share responsibilities. As an artist, Dafna Maimon suggests there are practical ways for institutions to collaborate, such as in booking residency stays instead of Airbnbs for artists or project related travel.

Curator and researcher Ki Nurmenniemi also speaks about the importance of building symbiotic relationships in the art ecosystem, including mutualistic symbiosis and systems of redistributing abundant resources.

“Not everyone has to become an institution”, argues Miina Hujala, an artist and curator, and member of the Reside/Sustain research project.

During that conversation a lot of ideas float around interaction with the local community: be it public, educational or other forms or events, with the main purpose of working with ‘fears’ that people might have around contemporary art (as people tend to be scared or feel pressure when they do not understand something).

“How can artistic activities be accessible to the local community, while at the same time maintain the desired intellectual level of the artist?”, asks Meri. “Does the local community need to like what we do? Maybe artists do not need to share everything?”, she adds. Dafna speaks about the gap between what the community understands about art and how artists understand art.

Perttu brings up the idea of layering – doing something for the community, but at the same time doing something different that interests you for your artistic practice alone.

Ki says that it also took a long time for the Hyrynsalmi community to accept Mustarinda. “These coffee/bun events helped build a connection”.

Perttu Saksa’s residency, for example, will soon function as a salon, open to the public – where concerts and readings and other events will take place, but which will also allow residency organisers to keep their own work private.

Meri says she will start her residency activities with a Milk party for the community on the 2nd of June.

The conversation slowly flows into discussions of doing and not doing, as well as learning and unlearning.

“Sometimes the most creative act is to do nothing”, says someone.

“We are not a bottle with labels of everything that we do”, Miina Hujala adds.

And then it is time to move along.

Artistic or creative community?

Next we travel to the village of Fiskars. This is the place where the famous company (of the same name) that produces home and garden wares, was created: from scissors to garden equipment, and recently also glass and ceramic tableware, since Fiskars acquired the production of both Iittala and Arabia.

As early as the 1980s the company began closing its local production sites, moving its factories to other regions and countries, for example, to Romania. In the 1990's the village of Fiskars began to decline, and the owner of the company decided to invite artists to the village of Fiskars, offering them free housing provided they would take care of the maintenance and restoration.

Gradually more artists began moving to Fiskars. Ten years ago, if you wanted to rent or to buy a house in Fiskars you had to prove that you were an artist.

Over lunch, we talk to Kati Sointukangas, a coordinator of Fiskars AiR. This residency was organised by the Cooperative of Artisans, Designers and Artists in Fiskars, in 2006. It mainly works with international artists and operates seasonally. Recently, Fiskars AiR has also been concerned by the environmental and climate crises and tries to apply more sustainable approaches to its practices, including resource sharing and protecting nature and biodiversity.

A few years ago the situation in the village began to change and now, in addition to the art community in Fiskars, the city is also attracting creative industries including local and organic food production. For example, we had lunch in a restaurant which serves only four or five dishes each day, cooked from local/seasonal/organic products when possible, and also caters to people with different kinds of dietary restrictions – something vegan, something gluten-free, something lactose-free.

Other new industries include a craft beer brewery and craft gin production, candle-making – and the development of a bicycle friendly infrastructure.

The Fiskars company still owns large areas of land and forests in the region, using some forests for logging and timber production, and some for conservation (including areas adjacent to the lakeshores). Local residents tell us that some roads leading to these forests have been recently closed down – now you can only get there on foot.

The town of Fiskars has indeed, a postcard-look, like a postcard which has not yet been printed on paper: two-storied houses from the late 19th - early 20th century sit by a river, there is lots of greenery, small cosy cafes and shops. As with all the other places we visited we wish we could have stayed longer, but we need to travel further South by South-West.

By the big water, in the Shell Strait

Our final destination of the day is the coastal town of Tammisaari, –which is also surprisingly famous for being the home of one of the best pizza restaurants in the country – on busy days the waiting line to its entrance circles around the whole square and it might take quite a while to get a table or your pizza ordered.

Here we visit an artist residency at Villa Snäcksund which is run by the Pro Artibus foundation where, with the support of the Ukraine Solidarity Residencies programme, Ukrainian artist Anastasiia Sviridenko was also staying. We enjoy some local lemonade (a self-made natural brew “sima” with raspberries) outside, right by the bay, which bears the name of Shell Strait, and speak of artist residency practices during the times of Covid and now, during times of war. We also visit the studio of Dafna Maimon and her partner, Ethan Hayes-Chute.

The day is wrapped up by a visit to the artist studio where Anastasiia Sviridenko shows us her work.

A trip back home to Helsinki, first on a bus and then on a train, it is around 8 pm, the sun is still shining brightly, we go out to dinner at a ramen place and talk about all of the ideas and impressions of the day.

Just one last trip left this week.